Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-26 15:05:00

“We have richer stories, we do nothing with them.” -Sidath Gajanayaka

“We have richer stories, we do nothing with them.” -Sidath Gajanayaka

Let’s face it; a few years ago, the young had more or less given up on our movies. It took an extraordinary revolution, by our scriptwriters and directors and even actors, to take us beyond the commercial/arty divide rampant in the industry, through a spate of productions that began with Ho Gana Pokuna and continued until Adaraneeya Kathawak and, now, Bennet Ratnayake’s Nela. If Ho Gana Pokuna takes you back to those days when movies about children were really for our children, and if Adaraneeya Kathawak and Nela take us back to that time when we truly enjoyed romances onscreen, it’s not because there weren’t directors and scriptwriters who were able to give us these movies back then, it’s because those directors and scriptwriters were unwilling to tread on what was generally considered to be forbidden territory. The same, incidentally, can be said of our vocalists and composers: who’d have thought that a song like ‘Saragaye’ was possible three years ago?

We go to the theatre because we want to escape the ennui of our everyday, banal lives. The young of today, who are more intelligent than those from my generation, know when they are being cheated; they want something new, even with other art forms. They are tired of expedience in the arts because they have ready access to the internet and because the internet provides them with answers to every question they have, except for questions which delve into their most potent inner feelings. Those feelings can only be satiated by works of art that try out something new. And the new artists they look up to are experimenting in exciting ways, targeting the young and with them the old as well; one year after ‘Saragaye’, for instance, Sanuka Wickramasinghe gave us ‘Perawadanak’, which as a young man told me seemed to be aimed at the middle-aged rather than the school-going demographic he came from.

This is worrying

But while these revolutions are happening and while our revolutionaries are being inspired by them, so much, that they are setting up their own schoolboy bands, shooting away their own cameras, and writing their own scripts for film festivals, there’s one segment or genre which has not yet been salvaged from the banality of yesterday; movies about our stories, or more specifically, about our HISTORIES. This is worrying, because for an industry to vindicate itself in the eyes of the people, it has to get this genre sorted out. Right away.

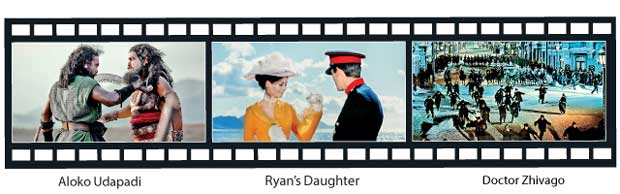

And with Aloko Udapadi, Chathra Weeraman tried to sort out the genre out last year. But even Aloko Udapadi, despite its minimal use of special effects and a commendable set of performances ranging from the exceptional (Roshan Ravindra) to the downright clichéd (Dharshan Dharmaraj), falls into the same trap that countless other movies about our history have fallen into. What Chathra’s film lacks are the histrionics about nationalism that so terribly and unsubtly beset other productions (even Jayantha Chandrasiri’s Maharaja Gemunu, not to mention Vijaya Kuweni, Mahinda Gamanaya, and Sri Dalada Gamanaya – it seems that I can’t remember ANY sequence from the latter three now – can’t quick get out of this fix), but what it unfortunately has in abundance are the American Cinemascope Epic-inspired sequences of savagery and ambitious cutting and editing that culminate in what I penned down in my review last year as ‘something the Wachowski Brothers could have perfected with some more CGI’ – the anthima vijayagrahani satana.

In Somaratne Dissanayake’s early works there’s an intelligent hand at work, turning the child actors into more than who they are

Aloko Udapadi is a grandiloquent monument to the eternal desire of our filmmakers to keep everyone satisfied through a big budget. Its manifest lack of overly ambitious special effects will keep the moderate moviegoer happy, but not the ordinary small town and village moviegoer, who will instead smile contently at the melodramatic romances and sequences of escape and treachery and, of course, swordfights and scenes of combat which, despite the subtlety of the special effects, are nevertheless inflated. It is, as Himal Kotelawala put it aptly, terribly unsubtle, though to me it’s also trashy in a strange way; its first half presents us with an interesting conundrum – how are you going to protect the Buddha Sasanaya without subverting the precepts in the holy texts? – but the directors and the scriptwriters don’t take us to the climaxes that this premise ought to have led us to in the first place.

When the truths get obliterated

When the truths get obliterated

We are “terribly unsubtle” about our children and our history this way because we treat them like we treat our wives and husbands and sons and daughters; we think we know who they are, and what they will do next, but we are shocked if not angry when they don’t behave the way we expect them to. In Somaratne Dissanayake’s early works, for instance, there’s an intelligent hand at work, turning the child actors into more than who they are. In his later works, however, he makes us expect blasts of emotion from them, and one after the other, that is what we get from his new child actors. It’s the same story with our history; we expect it to go from Point A to Point B smoothly with no disjuncture or detour, but we are shocked when an artist questions the conventional wisdom by laying down historical realities which we weren’t aware of. Like our wives and husbands, we want our stories to remain the way we want them to be (as laid down by our textbooks). What gets lost there is subtlety, and in the end, truths get obliterated and myths get perpetuated.

The Americans got away with this crime for decades because they weren’t raking up their own history, but instead appropriating them from other sources and civilisations, from Pagan Greece to Biblical Rome, appropriating them so well that we ignored the most basic flaws they thrived on (like how on earth could Charlton Heston ever be convincingly cast as Moses or, worse, El Cid?). When they went back to their stories, the writers had the luxury of working on a relatively recent civilisation that provided a multitude of ways and means by which reality could be embellished. Even David Lean, who moved away from his home country to Arabia and Soviet Russia, was channelling this peculiar trait of the early American filmmakers, D. W. Griffith and John Ford included.

For better or for worse

What our directors and writers of historical epics miss out is the fact that while trashy epics like The Robe and The Ten Commandments and even Ben-Hur lost their sense of complexity and proportion thanks to the money-saving and money-making processes unleashed by the Big Studios, the more worthy epics, which did not suffer this fate, like Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago and Ryan’s Daughter, had one inextricable common factor; the long shots and lengthy editing were compensated for by the material that grew out of these technical gimmicks. Despite the overdrawn sequences of silence in Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago, the camera never becomes a substitute for the landscapes; it’s merely a prop, and the material, the sense of grandeur, comes out of that. In her review of Renoir’s La Grande Illusion, Pauline Kael distinguished between two kinds of artistry in the movies; the one that brings the medium alive with self-conscious excitement, and the one that makes the medium disappear. For better or for worse, the historical epic belongs to the first of these categories – the latter is the category of a Pather Panchali, a Gamperaliya, an Anantha Rathriya, where only life is affirmed – because of which the moviemaker has to operate from the premise that what he is depicting, and projecting, is life made more grandiloquent and poetic.

Aloko Udapadi is a grandiloquent monument to the eternal desire of our filmmakers to keep everyone satisfied through a big budget

Because the epic genre is flawed in this respect, the director and the writer is treading on unfamiliar, dangerous territory; no matter how hard they try, they just can’t get their story out of the one-dimensionality that so often encumbers the genre they are in. That is why the artiste has to work from the characters and the surroundings he works on. Neither Lawrence of Arabia nor Doctor Zhivago would have succeeded the way they did if all they gave us were lovely visuals and melodies (even though both have visuals and melodies that we dream of and hum now and then). There was always a sense of artifice that was buttressed by a living, breathing reality, which in turn gave these movies life. The plotlines parsed, the characters clicked. They made sense.

I think we’re entering an exciting new era and form of pop culture, different from the pop culture that greeted us 20 years ago when Bathiya and Santhush released their first album, Vasanthaye. We’re seeing genres being redefined and re-contextualised by our artists, which is not a bad thing. No culture survived, not even the most puritanical, without being open to change. No culture can survive for long if it shuts out that change. Besides, the generation that grew up on Bathiya and Santhush did not have the kind of access to social media and the internet that the generation who are being entranced by Sanuka Wickramasinghe have, so the latter, who as I implied earlier are intelligent in more ways than one, want something new. I thus suspect that our historical epics will have to change, not because the young want to tarnish history, but because they are tired of transliterating the textbook to the screen.

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

US authorities are currently reviewing the manifest of every cargo aboard MV

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul