12 Oct 2020 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Following is a response to the article titled ‘The case for state-supported maternity leave benefits in Sri Lanka’, published on September 24, 2020, in Mirror Business, by Verité Research.

Following is a response to the article titled ‘The case for state-supported maternity leave benefits in Sri Lanka’, published on September 24, 2020, in Mirror Business, by Verité Research.

It is encouraging to see an emerging discussion on issues such as maternity leave benefits at a time when these rights are under challenge. Such discussions contribute to expanding the current understanding of the economy, especially from a gender equality perspective.

Maternity leave benefits are an important factor in recognising and valuing unpaid care work and its contribution to the economy. Importantly, it also ensures decent work and gender equality at work.

Maternity protection is therefore a fundamental labour right enshrined in key universal human rights treaties. They stipulate protective measures for pregnant women and for women who have recently given birth, including the prevention of exposure to health and safety hazards during and after pregnancy, entitlement to paid maternity leave, maternal and child healthcare and breastfeeding breaks, protection against discrimination and dismissal in relation to maternity and a guaranteed right to return to work after maternity leave.

While legal instruments for promoting gender equality and protecting women workers’ rights are expanding and being improved, there is an ever widening gap between the rights set out in national laws and their implementation.

As recognised by the International Labour Organisation, women workers’ rights constitute an integral part of the values, principles and objectives to promote social justice and decent work – fairly paid, productive work carried out in conditions of freedom, equity, security and dignity.

In a world where countries, including Sri Lanka, have pledged to provide equal opportunities for access to employment to men and women alike, pregnancy or motherhood should not constitute a source of discrimination in access to or continuation of employment.

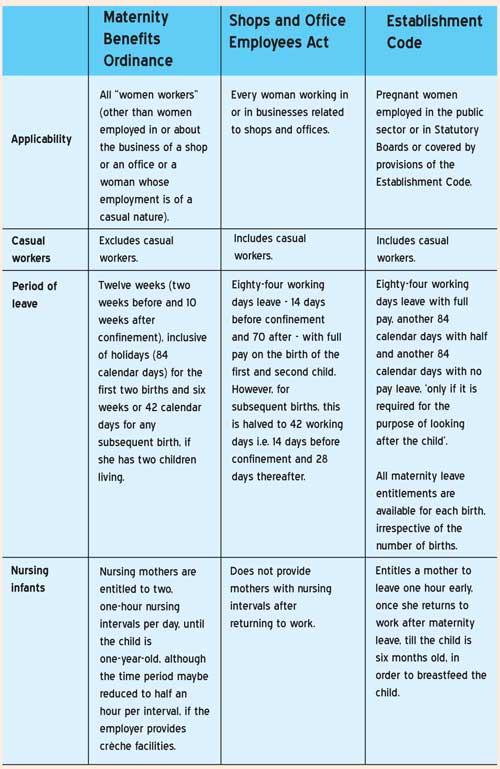

The principle laws governing maternity benefits in the private sector of Sri Lanka are the Shop and Office Employees Act No 19 of 1954 and Maternity Benefits Ordinance No 32 of 1939. The Establishment Code of Sri Lanka is the law applicable to state sector employees.

Accordingly, a woman’s leave entitlement differs merely by virtue of the sector in which she is employed and women placed in the same position due to pregnancy are treated differently. When the existing law is analysed, public sector women employees receive better benefits, compared to women in other sectors.

Sunethra M.E. Goonetilleke provides a comprehensive comparison of the existing legislation in her article ‘Maternity Legislation in Sri Lanka: Are Women Equal, Special or Different?’, published in Volume 11 of the OUSL Journal (2016). An excerpt of it is given in the table.

When women are discriminated due to their reproductive role or not provided maternity protection and when workers with family responsibilities are not protected, this directly affects their choices, especially for women. It places a higher burden on women as they attempt to juggle multiple roles with little support.

In fact, most countries today have recognised the role of the father in reproductive care work and have extended these benefits to men as well. The concept of parental leave therefore recognises the contribution of both women and men in caring for children. It also reflects the value a society places on care work.

However, the statutory requirements to afford women maternity benefits are not always welcomed by employers, who regard this as a ‘cost’ that takes away from their profits. Verité notes that this notion of maternity benefits as a cost, becomes an actual negative impact on young women during the recruitment process and recommends state support maternity benefits across all sectors as a solution.

However, the more critical issue here is the failure of employers to recognise the interdependence between the spheres of unpaid and paid work and the highly gendered understanding of care work as the sole responsibility of women.

For instance, while the ideas of ‘women’s empowerment’ and ‘equal opportunity’ are touted in the private sector, when it comes to recognising care work, it is either viewed as individual responsibility or that of the state.

Successful women are the superwomen, who can do it all through sheer ability and determination and care work is effectively viewed as confined to the private sphere of family and home and nothing to do with the workplace.

Encouraging employers to consider improving equality and well-being of their employees and of society as a whole, as primary functions of a healthy economic model, is necessary to shift the conversation from regarding rights such as maternity benefits as a cost and burden. It means that employers will recognise people’s multiple roles and understand the need to take those into consideration in ensuring decent work and equity in the workplace.

Women have to struggle post-childbirth physically, mentally and psychologically. Returning to their place of employment is for most women a stressful time in their lives. While most are resolved that they must take up paid employment again, they return to an environment where the work ethic takes priority, where they are expected to perform as per every other woman, including their non-childbearing colleagues.

If there is no paid maternity leave and the transition back to work after giving birth is too difficult, if not possible for many months, a woman might decide not to rejoin the workforce. In contrast, paid maternity leave ensures that the already trained and skilled work force is retained, which saves the cost of hiring and training a completely new individual. Parental leave, which includes men as well as women, goes a step further by recognising that care work is not the sole responsibility of women.

Hence, conceptualising paid maternal leave as an employer’s token of generosity is fundamentally flawed. We need to shift from the conservative economic perspective, which views reproductive and care work as external to the ‘real’ economy. Maternity benefits are not a ‘cost’ and a ‘burden’ on the employer. Women employees are not unprofitable because they are ‘a drain on resources’.

The recent decision of the government to reduce maternity benefits for new graduate employees shows that the current tendency is for even the state to cut back on hard-won benefits for women. Such regressive moves must be resisted at all costs.

Rather, there needs to be a clear understanding that both the state and private sector recognise and provide for women’s paid maternity leave. In fact, there should be realistic provisions for paternity leave as well. Both the state and private sector have a duty to facilitate care work in ways that reduce gender discrimination in the workplace as well as in the home. Ensuring maternity leave or rather parental leave is central in this regard.

24 Apr 2024 14 minute ago

24 Apr 2024 21 minute ago

24 Apr 2024 46 minute ago

24 Apr 2024 57 minute ago

24 Apr 2024 2 hours ago