Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-05-05 08:39:00

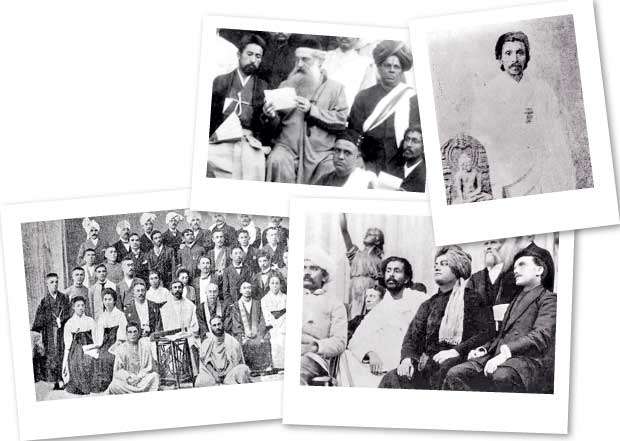

Sasanka Perera has recently introduced readers to a new book by Steven Kemper entitled Rescuing Dharmapala from the Nation (University of Chicago Press, 2015) – a book which surveys the socio-political activities of the Anagarika Dharmapala in a refreshing manner. I have yet to get hold of the book, but Sasanka provides enough commentary to provoke a discussion.

Within a context where Dharmapala aka Don David Hewavitarne is regarded as an influential Sinhala Buddhist chauvinist by many social scientists analysing Sri Lankan history and politics, Perera indicates that Kemper provides broader dimensions by re-situating Dharmapala “within the Buddhist world of his time by … focusing on his international activities in aid of Buddhist causes and cross-faith discussions.” Kemper’s new work, therefore, is a modification of the Protestant Buddhist thesis popularized in social science circles by Gananath Obeyesekere’s writings in particular.

Perera underlines these points:

“What manifests in Kemper’s descriptions of Dharmapala’s relentless travels and consistent speeches and writings are the dynamics of a tireless and almost single handed universalizing mission undertaken by an obstinately passionate man.”

“Dharmapala’s large-scale global institution-building programmes were focused on the larger project of realizing his dream of a united Buddhist world” – one which privileged Theravada Buddhism.

Thus, says Perera, Kemper “presents this enigmatic historical character in the complexity he deserves” – while adding, here, his (Perera’s) own caustic side-shot at the deficiencies in Amunugama’s recent compendium The Lion’s Roar.

During this welcome introduction to Kemper’s work, Sasanka Perera makes an important point: he highlights “the enormous power vested in private capital in spearheading [Dharmapala’s] religio-political mission.” Furthermore, this funding was not from NGOs, but “from individuals, which often meant himself.”

“Himself,” I add, meant the fortunes built up by his father Don David Hewavitarne and his brothers in the contracting, merchandising and furniture building trades during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Ironically, but not unusually, this means that the channels of capital formation and educational advancement in the English medium developed by the British colonialists in the nineteenth century paved the way for both Dharmapala’s world missionary outreach and his anti-colonial drive within Ceylon and India. These pathways have been illustrated previously in the researches of Ian Vandendriesen, KM de Silva, Kumari Jayawardena and others – including here my researches on elite formation.

Perera stresses that a “significant portion of the material used by Kemper to weave his narrative comes from Dharmapala’s unpublished notes and diaries collecting dust and disintegrating in neglected archives in India, which many Sri Lankan researchers hardly know of.” This comment is on the mark – but only partly. Perera does not seem to be cognisant of the fact that many of Dharmapala’s diaries are available in the Department of National Archives and the Maha Bodhi Society in Colombo.

Perera stresses that a “significant portion of the material used by Kemper to weave his narrative comes from Dharmapala’s unpublished notes and diaries collecting dust and disintegrating in neglected archives in India, which many Sri Lankan researchers hardly know of.” This comment is on the mark – but only partly. Perera does not seem to be cognisant of the fact that many of Dharmapala’s diaries are available in the Department of National Archives and the Maha Bodhi Society in Colombo.

The diaries are indeed a treasure trove. Working on the diaries for the period 1890-1915, I was able to fashion two articles in the late 1990s. As indicated in the title of one of these essays, viz., “For Humanity. For the Sinhalese. Dharmapala as Bosat Crusader,” the material within the diaries, supplemented by Dharmapala’s writings in Sinhala and English, enabled me to highlight the dual dimensions of the Dharmapala’s missionary and political zeal.

“For the Sinhalese” marks Dharmapala’s pro-Buddhist and pro-Sinhala endeavours together with their considerable chauvinist extremism. Both in his public canvas and in his diaries Dharmapala viewed the British and Christians as brutes, savages, demons, pagans and heathens. This was an inversion: he was deploying some of the verbal weaponry utilized by the British evangelists and ruling class in their readings of the “natives.”

However, in keeping with some of the writings in Sinhala in his day, Dharmapala also railed against the demala. the marakkala and the kocci. Rather innovatively, on one occasion he disparaged those whom he identified as “hambamarakkala” and on another occasion in 1911 even directed a diatribe at the kocci demala. Restrained to Calcutta during World War One, he fired off two virulently anti-Moor letters to the Colonial Office in London as soon as he heard of the tough measures the British took against the Sinhalese in suppressing the riots of mid-1915. This line of bias was set within a critique of British rule.

A striking strand in his thinking was a tendency to treat the subjectively-meaningful collective noun “Sinhalese” as equivalent to the category “Ceylonese.” In brief, the major part of the island’s population – that of his ethnic group – was rendered equivalent to the whole -- often in an unthinking and embedded manner. When associated with the prominent place commanded by the Sinhalese in the standard readings of the island’s history conditioned by the Mahāvamsa and many school texts in the British period, the political implications were deadly.

This thinking came to the fore in the “revolution of 1956” and subsequent island politics. Dharmapala’s political writings (in English and Sinhalese) and such texts as DC Wijayawardhana’s The Revolt in the Temple embodied the ideologies driving these politics. As we well know now, these currents, in their turn, heightened the collective identity of the Sri Lankan Tamils and eventually spawned the militant movement for Eelam in the 1970s.

Moreover, the diaries reveal that Dharmapala’s adoption of the Anagārika path of a Brahmacharya was linked to a self-perception of his life-path in the steps of the Buddha

My academic interactions at Peradeniya informed my pessimistic readings of the situation THEN in the early-mid 1970s. I was among those in Ceylon Studies Seminar circles at Peradeniya University who organised a full-day conference in Colombo entitled the “The Sinhala Tamil Problem” in early October 1973. That gathering only deepened my pessimism. In my reasoning the equation of “Sinhalese” with “Ceylonese” embodied previously in Dharmapala’s writings and holding sway among significant sections of the Sinhalese populace in the 1950s-70s was a fundamental factor bedevilling political compromise and promoting Tamil extremism. I drafted an essay in Heidelberg in 1976 which eventually appeared in the journal Modern Asian Studies in 1978 and indicated that Tamil militarism was around the corner. It gives me little pleasure to point to this article and tell people today: “I told you so.”

In this segment of my article I deployed the material Dharmapala’s diaries in several ways. I showed that the influence of Orientalist thinking and Protestant values in Dharmapala’s thinking argued for by Obeyesekera et al was, indeed, powerful. For instance, Dharmapala valued “science,” espoused a work ethic and railed against the “uncleanliness” of the Sinhalese and their attachment to yaktovil (exorcisms).

But the diaries also reveal his engagement with such Buddhist texts as the Visuddhimagga and the jātaka stories over the course of time. They display the emergence from 1899 of his intellectual dissension from Colonel Olcott’s line of emphasis and his hostility to Annie Besant’s interpretations within the world Theosophy movement.

Moreover, the diaries reveal that Dharmapala’s adoption of the Anagārika path of a Brahmacharya was linked to a self-perception of his life-path in the steps of the Buddha. At his first visit to Buddha Gāya on 27th February 1891, he wrote: “This morning at 4 I pledged myself to work for Humanity.” … and a little later he records this commitment: “I have to decide on the 17th inst. as to what life I should take and I decide it now. Bodhisatva life. Pure life and work for Humanity” (d/e 4 Sept. 1893) This meant a rejection of renunciatory asceticism in favour of bosat work in the world. It meant an emphasis on “purity’ and a rejection of “selfishness.” It involved a constant inner battle with his own sexual desires – such as those instigating masturbation.

“May I remain pure, pure, pure. There is much work to be done and I must be consciously pure in my thoughts” (d/e 26 July 1909, emphasis his)

“Last night [my] mind was disturbed by polluting sensual thoughts. When will this filthy body become emancipated from low desires? There is no possibility of my ever taking the sensual life. Nevertheless, disturbing tendencies at times overpower the higher nature” (d/e 14 June 1907)

As I argued then, the terms “pure” and “morality” in Dharmapala’s usage can be considered renderings of the Buddhist concept of Suddha, which denotes virtue in thought, word, and deed. Linked to this tenet is (was) the concept of sila, the externalization of Suddha through injunctions supporting purity in word and deed.

Studying the Dharmapala diaries was a revelatory and educational process for me as researcher. Though his terminology presented a Victorian and Orientalist flavour, it became clear that his readings of the world were directed by Buddhist ethics more than Protestant puritan values.

“Dharmapala set forth on the Bosat path of the Buddha to reclaim Bodh Gaya, to spread the Dhamma in India and the world, to serve “Humanity,” and to revive Sinhala Buddhist society: “My life is pledged to the Cause of Humanity. May I be born again and again to help the Sasana. I will follow the footsteps of the Lord of Compassion” (d/e 18 July 1894, emphasis added). The reiteration is worth reiteration: his mission for humanity was to be in “all [his] incarnations,” “life after life” (d/e 27 Feb. 1891; 5 June 1894). “

In brief, this line of argument would seem to complement Kemper’s apparent emphasis on the importance of Dharmapala’s overseas engagements and his missionary zeal towards spreading the Dhamma. The diary data also enables one to identify the thinking that underlay such massive efforts.

In my reading the seminal moment in his career arose during his first visit to Bodh Gaya in February 1891. To repeat: “This morning at 4 I pledged myself to work for Humanity . . .” (d/e 27 Feb. 1891). It was then that he committed himself to the path of a homeless (anagārika) celibate missionary -- that is, a brahmacharya.

In a speculative leap, I go further. I suggest that Bodh Gāya (or Buddhagāya) was not merely an inspirational driving force for Dharmapala. It was a magical destination: by restoring Buddhism in this primordial spot Dharmapala hoped that the wonderful messages of Buddhism would conquer the world. Plant that wonderful seed in its birthplace and, hey presto, Buddhism would be disseminated throughout the contemporary world. This wonderful faith would be a world conqueror like Asoka. Mount Meru would be reincarnated.

This is a thought that I cannot substantiate. My work on the diaries was way back in time and the material is not at my fingertips. But it is a thought that has been lurking in the recesses of my brain. I present it to provoke. The ‘provocation’ is directed at Kemper in particular: he has been one of the few to work on the Dharmapala diaries and he has done so recently. I await his response eagerly as I venture out to get my hands on his book.

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

US authorities are currently reviewing the manifest of every cargo aboard MV

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul