Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-05-11 03:39:00

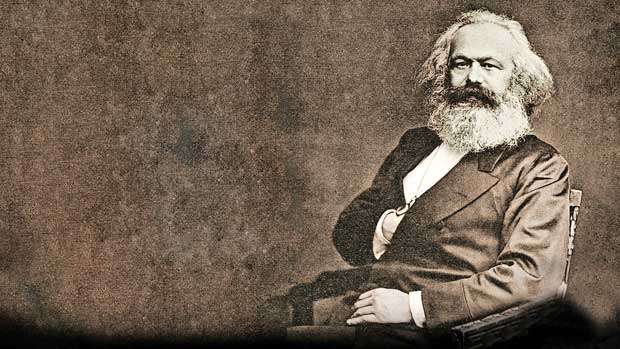

In hindsight, it wasn’t just the capitalists who got it wrong about capitalism. The Marxists got it wrong too. Being a product of Judeo-Christian values and of Western philosophy, it was fated to view the world in terms of inputs and returns. One can of course argue that it was because  Marxism was implemented in countries which had not passed the feudal stage of their historical development that it failed as an ideology, but regardless of the imperatives of history, I can only quote Regi Siriwardena here: “The alternative to [poverty] isn’t unlimited plenty.” Therein lies the tragedy of Adam Smith and Marx; they assumed a world that did not, and in reality, could not exist. Roughly the same argument can be made of that other ideology which, though born from the wellsprings of capitalism and industrialisation, in later years flamboyantly sought to combat the ills of the free market and profit motive -- namely, liberalism.

Marxism was implemented in countries which had not passed the feudal stage of their historical development that it failed as an ideology, but regardless of the imperatives of history, I can only quote Regi Siriwardena here: “The alternative to [poverty] isn’t unlimited plenty.” Therein lies the tragedy of Adam Smith and Marx; they assumed a world that did not, and in reality, could not exist. Roughly the same argument can be made of that other ideology which, though born from the wellsprings of capitalism and industrialisation, in later years flamboyantly sought to combat the ills of the free market and profit motive -- namely, liberalism.

Fernand Braudel (in my opinion the greatest historian of the previous century, who surveyed the global economic landscape and its evolution) writes in his three-volume magnum opus, Civilization and Capitalism, that the 15th and 18th centuries, coming before the coming of the Industrial Revolution, saw the differentiation of Western Europe into three types of economy; the material life, which consisted of barter trade and self-sufficient agriculture (“within a very small radius”); the market economy, which consisted of transactions between producers and consumers; and the world of speculation, underhand transactions, manipulation, monopolies, and corporations.

Fernand Braudel (in my opinion the greatest historian of the previous century, who surveyed the global economic landscape and its evolution) writes in his three-volume magnum opus, Civilization and Capitalism, that the 15th and 18th centuries, coming before the coming of the Industrial Revolution, saw the differentiation of Western Europe into three types of economy; the material life, which consisted of barter trade and self-sufficient agriculture (“within a very small radius”); the market economy, which consisted of transactions between producers and consumers; and the world of speculation, underhand transactions, manipulation, monopolies, and corporations.

Direct observation of so-called economic realities, between the 15th and the 18th centuries... did not seem to fit or even flatly contradicted the classical and traditional theories of what was supposed to have happened

“Direct observation of so-called economic realities, between the 15th and the 18th centuries... did not seem to fit or even flatly contradicted the classical and traditional theories of what was supposed to have happened,” Braudel noted in the first volume. Capitalism, he surmised, had been touted by these theories as the product of free market exchanges, when in reality it was given life by the speculator: “So in the end, people believed, rightly or wrongly, that exchanges play a decisive role as a balancing force, that through competition they smooth out uneven spots and adjust supply and demand, and that the market is a hidden and benevolent god, Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’, the self-regulating market of the 19th century and the keystone of the economy, as long as one sticks to laissez fain, laissez passer.” In other words, “laissez-faire” was a creature of dubious genesis; modern textbooks look towards the market exchange as the source and wellspring of it, when it was actually created and sustained by the profiteer who operated on an asymmetry between the producer and consumer.

The middle class in England rose after the Reformation and the Glorious Revolution which turned Britain into a constitutional monarchy

The irony was that this myth wasn’t really propagated by the likes of Adam Smith (after all the term “invisible hand”, which we associate with him today, is mentioned only once in his Wealth of Nations), but rather by later intellectuals and economists who probably saw in that myth a rationale for their worldview. So when even a “liberal” economist like Paul Krugman argues that there is no alternative to child labour in developing countries, he is foregoing on the fact that such problems can be remedied by State-led initiatives to, for instance, set up a cohesive national industrial sector. This is the point that Avocado Collective makes in their second riposte to Advocata; that colonial societies like ours were “blessed” with an entrepreneurial class which just couldn’t think beyond the easy money of the plantation sector.

The alternative to [poverty] isn’t unlimited plenty. Therein lies the tragedy of Adam Smith and Marx; they assumed a world that did not, and in reality, could not exist

Affirmative action, on the part of the government, doesn’t just make sense, it is also the only way through which centuries of economic imperialism can be done away with and cured. Economic myths, repeated over and over again, can only have the effect of keeping us in our proverbial place; the poor countries get poorer, the rich countries get richer.

Moving on. It was the reality, and not the myth, of free markets (as per Braudel) which gave birth to liberalism. Marx got a lot of things wrong, but one area where he got it right was his contention that history was a series of class struggles. Viewed this way, the era immediately preceding the pre-capitalist phase of economic history, i.e. right until the 10th century, was one of ceaseless conflict between landowners and peasants, in turn exacerbated by the many plagues which wrought themselves on the continent. The concept of liberty, specifically “liberties” as Braudel put it, gained currency after the 12th century as and when powerful groups of vested interests waged war against other less powerful groups. The peasants, who have always been at the worse end of the deal, nevertheless prospered during times of economic booms, since capitalism did not yet differentiate at this (infertile) stage of historical development between those who toiled and those who profited from that toil. The evolution from “liberties” (encompassing many groups) to “liberty” (encompassing, ostensibly, the whole of humanity) was rooted in the evolution from cities to territorial states, from the Renaissance to the Reformation; viz., from labour to capital. The world, until then validated through divinity, was now rationalised through science and mathematics.

Affirmative action, on the part of the government, doesn’t just make sense, it is also the only way through which centuries of economic imperialism can be done away with and cured

Liberalism was the definitive synthesis of the theism of the centuries preceding industrialisation and the rationalism of the centuries following it. It was the rationale which brought the church, the state, and the industrialist together. In that sense, it denoted three different meanings: the political (limiting the power of the executive in favour of the legislature and judiciary), the economic (limiting the intervention of the state in relations “between individuals, classes, and nations”), and the philosophical (calling for freedom of thought and freedom from coercion). All three dimensions, at least initially, became a perfect cover for the rising bourgeoisie: the political because the legislature and judiciary were housed by the new bourgeoisie, the Whigs; the economic because it exculpated the pursuit of profit; and the philosophical because it provided a smokescreen for the emergence of a new bourgeois consciousness (in the first few decades, for instance, “liberalism” did not include the right to vote, since the propertied class which had birthed it opposed universal suffrage; the likes of Smith believed that if the suffrage be extended to the masses, they would elect opportunists and demagogues who would subsequently overthrow the institution of property).

Property; this, more than anything else, was what defined the economic history of Western Europe, indeed of Europe in general. Liberalism flourished in the areas where property relations were sanctified with reference to rights and concomitant duties, to freedoms and concomitant obligations. In areas where feudalism did not give way to capitalism after the 16th century, such as much of Eastern Europe, liberalism did not emerge, which explains their economic backwardness even today. The 14th and 15th centuries, moreover, saw the overthrow of the absolutist theocratic state (theocracy, a term used to describe and disparage the Middle East today, was very much a reality in the West then), subsumed the fanatic fervour of the Papacy in the “rationalism” of Thomism and Hugo Grotius, the latter of whom famously quipped that natural law (the foundation of the modern state) would exist even if God didn’t, and provided the perfect backdrop to the institution of private property. The bourgeoisie were here the first revolutionaries, long before the proletariat, since they were more successful than the proletariat at capturing political power under the guise of preserving natural law.

The English middle class, Engels wrote in his introduction to “Socialism: Utopian and Scientific”, were wary of looking at the world through a materialistic lens, despite the fact that materialism was born in England. It was a defence mechanism at one level, used in order to compensate for their bourgeois guilt. Engels elaborates on this culture of guilt in an interesting way, depicting it as the result of the Lutheran-Calvinist Reformation in Europe. The middle class in England rose after the Reformation and the Glorious Revolution which turned Britain into a constitutional monarchy. They reacted against the secular revolutions which unfolded throughout the rest of the region, particularly France, and they were wary of pre-industrial philosophies which were used to rationalise the absolutist state (in particular, Hobbes’s Leviathan). This middle class thus sought a way to reconcile their materialist past with a more deist worldview. Deist, because theism assumed a creator who would intervene in material, secular affairs, while the new bourgeoisie needed a doctrine of a creator who did not.

For obvious reasons, the philosophy which appealed to them the most here, shorn of the dualistic world (of evil and upheaval on the one hand and order and continuity on the other) envisioned by Thomas Hobbes, was the liberalism of John Locke. It was to Locke, the “liberal” owner of stocks in slave trading companies, that the industrialists of the new era turned to get away from their secular past. While Hobbes had framed the social contract between the ruler and the ruled as an antidote to a brutal “state of nature” which had existed before it, Locke conversely framed this “state of nature” as an Eden before its Fall: a golden age which could not survive the exigencies of the world without one vital element. Property. Liberalism, the darling of the industrial bourgeoisie, was the product of this line of thinking. It was a reaction against a largely materialist past, and a response to the need for a synthesis of divinity and rationality.

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

US authorities are currently reviewing the manifest of every cargo aboard MV

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul