09 Aug 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The acquittal of Dr. Shafi Shihabdeen, the unquiet return of several Muslim Ministers to the Cabinet, and the leadership tussles in the UNP, SLFP, and SLPP have turned the tables on the head of the local Catholic Church, Archbishop Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith. This is inevitable in a country where the popular consciousness can turn yesterday’s hero into today’s zero. The gradual, yet in one sense rapid downturn of the Cardinal has, however, been missed by the news, since the media continues to project his heroism: if not subtly, then overtly. My belief is that the changing layers of popular opinion regarding him, and his public statements, reveal the class divisions that seem to be missed by those who either inflate or downplay what he has done. His halo has begun to slip, but this does not, and should not, mean it was there in the first place to begin with.

Athuraliye Rathana Thera’s fast was the continuation of a long line of similar protests that subverted legal and parliamentary procedures in the hope of (for the lack of a better way of  putting it) getting something done quickly. From the satyagraha against adopting Tamil as an official language in 1958, to the opposition against the UNP’s agreement with the Federal Party in 1965 (which led to the shooting of a protesting monk, something that would probably never happen today), to the demonstrations against the LTTE and against making concessions to the LTTE and pro-LTTE lobby, the Buddhist clergy has since independence represented the interests of more populist sections of the petty bourgeoisie. When Cardinal Ranjith made his appearance at Rathana Thera’s fast, he was thus doing something unprecedented; he was, in effect, uniting these populist sections of his flock with those of the Thera’s.

putting it) getting something done quickly. From the satyagraha against adopting Tamil as an official language in 1958, to the opposition against the UNP’s agreement with the Federal Party in 1965 (which led to the shooting of a protesting monk, something that would probably never happen today), to the demonstrations against the LTTE and against making concessions to the LTTE and pro-LTTE lobby, the Buddhist clergy has since independence represented the interests of more populist sections of the petty bourgeoisie. When Cardinal Ranjith made his appearance at Rathana Thera’s fast, he was thus doing something unprecedented; he was, in effect, uniting these populist sections of his flock with those of the Thera’s.

I mentioned last week that the Cardinal looks to, and channels the grievances of, a subsection of the Catholic community which happens to make up a very sizeable majority. This was the subsection that made figures like Rev. Fr. Marcelline Jayakody and Rev. Fr. Ernest Poruthota, as well as radicals like Rev. Fr. Tissa Balasuriya, popular; it was what made the nationalisation of Catholic schools possible (in early 60s the LSSP and the Communist Party rallied support for nationalisation from the Catholic belt from Wattala to Puttalam); and it was what brought the Catholic clergy and Buddhist clergy together on a common platform against separatism. For obvious reasons, the Westernised liberal intelligentsia and upper echelons of Catholic society differ sharply with these segments, because of their social conditioning.

The more affluent sections of the Catholic community, if I may put it as a part-Catholic myself, have become more Protestant than Catholic: they are hostile to leadership figures and they do not believe in the infallibility of clergymen. The poorer sections, like their Buddhist counterparts, by contrast still hold on to the Cardinal; that is what led one child, interviewed on TV about the schools closure, to exclaim “I do what the Cardinal tells me!”

"The Cardinal in the final assessment, stands out neither as a hero nor as a villain. As Nietzsche would have said, he is human, all too human. Nietzsche also said that there was only one Christian, and he died on the Cross"

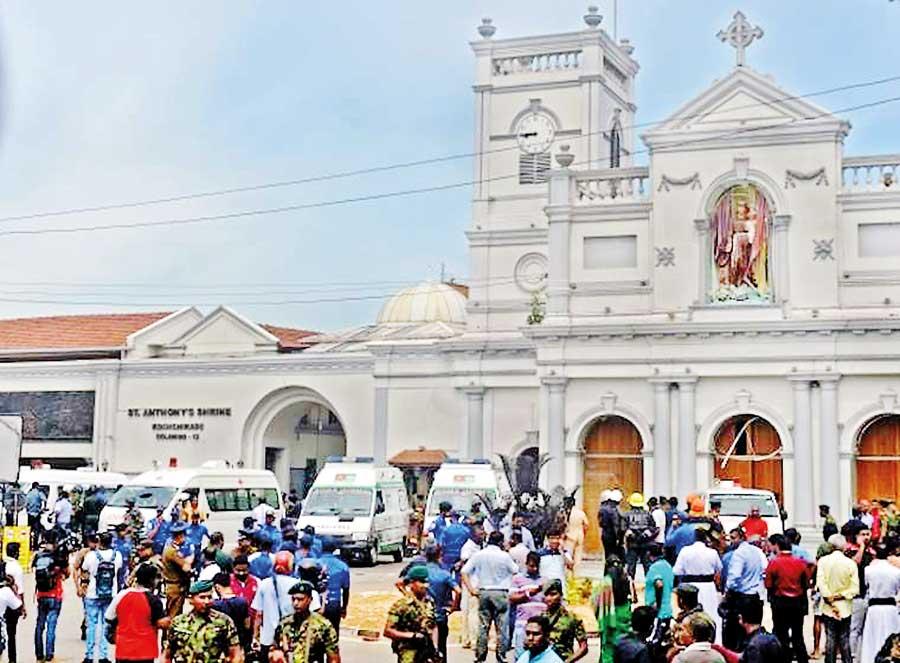

Such gentleness and innocence is lost upon the Catholic upper classes, for whom neither Cardinal Ranjith nor the radical segments of the Catholic and Buddhist clergy are befitting of respect, honour, or the courtesy of an audience. This is the same class who would declare, forthrightly, that it was not the Cardinal but their sense of decency which restrained them from attacking other communities after the April 21 attacks, refusing to acknowledge the role played by a man who some argued was worthy even of a Nobel Prize. That they would rather listen to, and defend, ministers who lash out against Buddhists over a man who did what he could to bring the country together tells us a lot about their preferences.

To be sure, Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith has a past. H. L. D. Mahindapala may call him “the benign star of Sri Lanka” who deserves being defended against detractors like Shyamon Jayasinghe (who argues that the Cardinal has consistently breached protocol with statements issued after April 21), but defending him while ignoring that past is as fallacious as claiming that he’s using the Easter Sunday attacks to bolster his image. According to Wikileaks, to begin with, he was at the forefront of the campaign to lobby the US government to drop charges of war crimes and not press the accountability button; a few years later, there were allegations that he supported the Rajapaksas, especially when his niece was posted to Paris months before the Pope’s visit; most discernibly though, there was and is his stance on censorship, secularism, human rights, and the death penalty, which provoked a backlash from nearly everyone and anyone.

"Some argued it was worthy of a Nobel Prize for Cardinal for his peace-making efforts"

But then none of this can deny the importance of a milieu which has lent him support. The Catholic lower middle class, consisting of lower level professionals, merchants, and artisans, are not unlike their Buddhist counterparts. Temperamentally, they are both conservative and militant; they continue to project an ethnic along with a religious identity, which is how they formed a part of the Sihala Urumaya after Rev. Fr. Oscar Abeyratne, who founded the Kithu Dana Pubuduwa, gave support to the party in the Catholic belt from Negombo to Puttalam; and they form the crest of the non-Buddhist milieu that affirms nationalism, though we may never know for sure (their political preferences are more ambivalent).

The same can be said of the Catholic peasantry in coastal areas beyond Moratuwa, whose exposure to Buddhism has led to a sort of syncretism between their tenets and those of a faith which, historically, has diverged from it on cultural and political grounds. Indeed, if one is to look for inter-ethnic and interfaith dialogue, Negombo and Chilaw might be a good place to start – if it weren’t for the supposedly more liberal affluent wing of the community opposing the idea of such a syncretism on the grounds of, of all things, religious autonomy. (When a photo of Catholic students worshipping priests at a school prize giving ceremony went viral on social media, and found favour with those for greater cultural cooperation between the two communities, a segment of this liberal affluent wing publicly criticised it, implying that it was an act of cultural compromise – when in reality it was one of cultural fusion.) Not surprisingly, the apathy of this liberal and affluent wing of the Catholic community has brought it into conflict with the Cardinal, even if, after the attacks, the mirage of consensus within that community seemed to bring them both together before him. This apathy has, more often than not, blinded the anti-clerical Catholics to the real implications of what he has done, what he has said, and what he has chosen not to do or say. To give just one example, one of the more persistently made accusations against him is that he provoked if not stoked Islamophobia by demanding that Catholic schools be shut down for weeks. The delay in opening those schools may (not) have provoked such resentment – who can say for sure? – but surely, even if this were the case, how was it that these critics were unaware of the fact that his decision served, at one level, to benefit poorer students who tend to come to school by public transport and thereby open themselves to a bigger risk of a terrorist attack? Those who resort to private transport risk next to nothing in comparison; by making blunt assessments of the Cardinal’s supposed hysteria, they were only making their ignorance of the plight of their less privileged brethren starkly, nakedly evident.

The same can be said of the Catholic peasantry in coastal areas beyond Moratuwa, whose exposure to Buddhism has led to a sort of syncretism between their tenets and those of a faith which, historically, has diverged from it on cultural and political grounds. Indeed, if one is to look for inter-ethnic and interfaith dialogue, Negombo and Chilaw might be a good place to start – if it weren’t for the supposedly more liberal affluent wing of the community opposing the idea of such a syncretism on the grounds of, of all things, religious autonomy. (When a photo of Catholic students worshipping priests at a school prize giving ceremony went viral on social media, and found favour with those for greater cultural cooperation between the two communities, a segment of this liberal affluent wing publicly criticised it, implying that it was an act of cultural compromise – when in reality it was one of cultural fusion.) Not surprisingly, the apathy of this liberal and affluent wing of the Catholic community has brought it into conflict with the Cardinal, even if, after the attacks, the mirage of consensus within that community seemed to bring them both together before him. This apathy has, more often than not, blinded the anti-clerical Catholics to the real implications of what he has done, what he has said, and what he has chosen not to do or say. To give just one example, one of the more persistently made accusations against him is that he provoked if not stoked Islamophobia by demanding that Catholic schools be shut down for weeks. The delay in opening those schools may (not) have provoked such resentment – who can say for sure? – but surely, even if this were the case, how was it that these critics were unaware of the fact that his decision served, at one level, to benefit poorer students who tend to come to school by public transport and thereby open themselves to a bigger risk of a terrorist attack? Those who resort to private transport risk next to nothing in comparison; by making blunt assessments of the Cardinal’s supposed hysteria, they were only making their ignorance of the plight of their less privileged brethren starkly, nakedly evident.

"When Cardinal Ranjith made his appearance at Rathana Thera’s fast, he was thus doing something unprecedented; he was, in effect, uniting these populist sections of his flock with those of the Thera’s "

There’s more I can write, but unfortunately, spatial constraints restrain me.

Cardinal Malcolm Ranjith, in the final assessment, stands out neither as a hero nor as a villain. As Nietzsche would have said, he is human, all too human. Nietzsche also said that there was only one Christian, and he died on the Cross; without extrapolating this to present circumstances, let us concede that there’s no one, clergyman or layman, Buddhist or Catholic, who can claim a moral upper hand here, now. Those who provoke Islamophobia are hence as much to blame as those who provoke resentment among racists; the so-called lower orders are hence as much to blame as the supposedly more refined upper classes.

Once we account for the fact that no one is perfect, that we are as Christian or Buddhist as the man, woman, and child next to us, perhaps we will be able to appreciate what the Cardinal has managed to, inadvertently, bring about: a rallying of popular forces from his community along with those from a community which has historically found more reason to diverge from, than converge with, those he represents. In this, he is a radical, despite the many anti-radical positions he has taken, is taking, and probably will continue

to take.

26 Apr 2024 1 hours ago

26 Apr 2024 2 hours ago

26 Apr 2024 3 hours ago

26 Apr 2024 3 hours ago

26 Apr 2024 5 hours ago