Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-17 02:11:00

Market logic is based on the principles of profit. Not all aspects of our lives can be assessed by the profit lens. Using this lens to determine education policy has meant that the humanising and civilisational goals of education, such as ensuring equality and producing the kinds of citizens necessary for maintaining a democratic and pluralistic society are being undermined

Market logic is based on the principles of profit. Not all aspects of our lives can be assessed by the profit lens. Using this lens to determine education policy has meant that the humanising and civilisational goals of education, such as ensuring equality and producing the kinds of citizens necessary for maintaining a democratic and pluralistic society are being undermined

One of the most polarising issues being debated in relation to education currently is that of the virtues of State vs Non-State education. Dr. Saman Kelegama’s speech at the J.E Jayasuriya Memorial Lecture this year, proposes that Sri Lanka needs to move beyond this debate and accept the need for non-state education as a viable alternative to the crisis in the state education sector.

Dr. Panduka Karunanayake’s response to my earlier article, also touches on this issue. Whatever the State of the debate on this issue, what is happening is that successive Governments, with the support of the World Bank have been preparing the ground work for the entry of non-State educational institutes particularly in the higher education sector.

Policy prescriptions and education reforms are heading in the direction of non-State higher education, sweeping aside any debates.

Dr. Kelegama’s position (And of many others) is that as long as quality can be assured, non-State educational institutions should be encouraged.

Yet, what the SAITM controversy is showing us is precisely the difficulties in assuring quality.

Degrees leading to professional qualifications such as law, medicine and engineering in addition to being subject to evaluation of academic bodies such as the UGC, must also adhere to guidelines set by professional bodies responsible for maintaining standards in that field.

Another aspect that is overlooked in the discussion on quality assurance and accreditation processes is the potential for corruption.

We don’t have to look much further than to our close neighbour India in order to ascertain the potential for corruption in education.

Standardisation and establishment of institutions is not a guarantee that the process will be corruption free. When there are large sums of money involved (And education has already become a highly lucrative sector) the potential for corruption is high. Even as it is now, corruption has entered the education system in Sri Lanka.

Yet, we have been able to maintain some degree of trust in the examination system and the quality of education. Further financialisation of the sector will simply increase opportunities for corruption.

If the private health system and private transport system in Sri Lanka are examples to go by, we have extremely weak regulatory mechanisms. Our systems for investigating and prosecuting  corruption are practically non-existent.

corruption are practically non-existent.

Panduka’s argument is somewhat broader. He proposes that the State/private dichotomy is no longer valid and that the private sector or the market is not quite as evil as I have painted it out to be. Indeed, in that sense, what meaning is there in the dichotomy between state and non-state educational institutions?

The blurring of this dichotomy is not an accident of history. It is linked to the policy prescriptions associated with neoliberalism which is a distinct phase of Capitalism which we have been experiencing for the last three to four decades globally.

Neoliberalism demanded that all processes and institutions be subject to the principles and laws of the market. Education was one such field. Thus, this debate is not simply about the merits and demerits of delivery of education by the State Sector vs the Private Sector. It is about how the meaning and purpose of education has been redefined by neoliberalism.

The neoliberal turn in education, has meant that whether public or private, education is driven by market demand and corporate culture. It has been accompanied by cuts in public expenditure on education and the demise of study programmes that are considered unnecessary by the market.

The most affected disciplines in this regard are the social sciences and humanities which have either been considered unnecessary or mere appendages that provide ‘soft skills’ to the more important (Profitable) disciplines such as medicine and technology.

My argument against this neoliberal turn in education is not simply about the evils of the market. It is about an ideology that suggests that market principles are the primary determinant of what is good and necessary for society.

Market logic is based on the principles of profit. Not all aspects of our lives can be assessed by the profit lens. Using this lens to determine education policy has meant that the humanising and civilisational goals of education, such as ensuring equality and producing the kinds of citizens necessary for maintaining a democratic and pluralistic society are being undermined.

Teaching of philosophy, history, religious studies, art or literature might not be profitable – but they are necessary for shaping the kind of society in which we want to live. Neither can the depth and breadth of these disciplines be packaged into ‘soft skills’ courses that are the current rage in the education sector. The neoliberal turn in education has also affected disciplines other than the humanities and social sciences. The emphasis on cost-effectiveness for example has led to drastic changes in how we teach and how students and the faculty are assessed. The obsession with ranking; rewarding publications over teaching; loss of collegiality and forms of sociality in educational institutions; the loss of flexibility in curricula and study programmes are some of those consequences.

Also, contrary to what Panduka suggests, the more ‘political’ approach to education is not confined to the work of John Dewey. It forms part of the critical tradition in educational theory known as Critical Pedagogy.

Critical pedagogy basically argues that education has an emancipatory role and is therefore inherently political. In fact, sociologists have long argued about the political role of education: education is not simply about imparting knowledge – in modern society, education is one of the most influential socialisation systems. The socialisation process is based on particular values in specific societies and they often reflect the values of the elite of that society. Thus, there has always been and always will be a political meaning to education.

The question is not whether education is political or not, but rather which political ideology, economic and socio-cultural system a particular education system sustains.

Dismissing critics of the market driven approach to education as ‘political’ or ‘politically manipulated’ assumes that those promoting a market driven approach to education are politically neutral and above manipulation. This is far from correct.

Panduka also suggests that freeing up the education to the private sector serves to democratise education. This perhaps stems from the idea of providing more choices from which the individual then is able to select what he or she wants. Wonderful as that sounds, in reality these choices are far from free or democratic, if democracy is also about equality of opportunity.

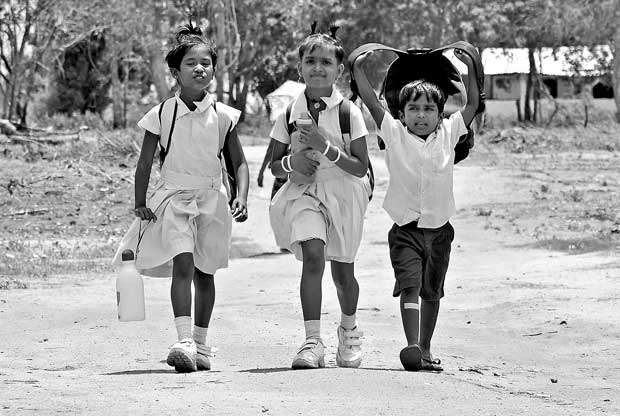

Recently, when I called one of my regular three wheeler drivers (whom I shall call Sarath), he said he was unavailable. The next day when I met Sarath, he explained that he had taken his son for Karate classes to Kottawa. He went on to say that the school only has time for one hour of Karate per week and hence the Karate teacher had asked the students to come for extra classes to his house.

I was aware that Sarath had struggled to get his son into this particular school (Quite a well-known school in Colombo) and that he had in fact had to ‘donate’ some equipment to the school before his son was admitted. Sarath said that a significant proportion of his income was spent on his son’s education. Sarath’s story is not at all unusual.

These are the everyday consequences when the burden of education is shifted to individuals and families. This also means that the price you are willing to pay determines the quality of the kind of education you will obtain. Sarath’s children certainly cannot afford the top end in the range of tuition classes and Karate coaching that the market has made available.

There are other children at the school who can and will almost inevitably therefore do better than Sarath’s children.

How is such a system contributing to democratising education?

The debate on the entry of the non-State Sector into education is not simply about, who delivers education. It is about the nature of education.

Further, calling the entry of the private sector into education as ‘non-State’ masks the commercial interests that lies at the heart of the matter behind the surge of interest from the private sector in investing in education.

What we are seeing today is naked commercial interest in the education sector. And indeed, that is how the market works: it moves to where there is profit to be made. And certainly, there is money to be made in education – and lots of it. The question here is whether education that is based on profit can fulfil those broader goals of education that are not simply about individual advancement, but of society in general.

adhil kamaal Friday, 17 March 2017 04:37 PM

very good article about education.iam expect more article

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul

A recent post on social media revealed that three purple-faced langurs near t