Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-19 05:41:00

This country has seen scores of elections (general, presidential and other) since its independence in 1948. But the three bloody rebellions by its youth (two in the south, and one in the north) have been crucial in shaping the country’s psyche more than the sum of all these elections. They are political barometers by which our political climate can be judged.

The Tamil rebellion in the north, popularly known as the ‘Eelam Wars’, gained wide international exposure, and many accounts of it were written by Western and Indian writers, while there are several books by Sri Lankan authors, too. The JVP’s first rebellion in 1971  led by Rohana Wijeweera did not gain the same international exposure, but a few important accounts of it are available, written by high level participants as well as a judge. The JVP’s bloodier second rebellion (1987-90) is murkier. No high level participant wrote any account of it. Most were killed, and the few remaining have bloodied hands, a factor which could prevent them from writing. There has been extensive newspaper journalism but these accounts are mainly about the detention camps and torture chambers where thousands of JVP members (and others not connected) were held and put to death. There has been no work giving us the bigger picture, reconstructing the history of these violent and chaotic years in an analytical and coherent manner.

led by Rohana Wijeweera did not gain the same international exposure, but a few important accounts of it are available, written by high level participants as well as a judge. The JVP’s bloodier second rebellion (1987-90) is murkier. No high level participant wrote any account of it. Most were killed, and the few remaining have bloodied hands, a factor which could prevent them from writing. There has been extensive newspaper journalism but these accounts are mainly about the detention camps and torture chambers where thousands of JVP members (and others not connected) were held and put to death. There has been no work giving us the bigger picture, reconstructing the history of these violent and chaotic years in an analytical and coherent manner.

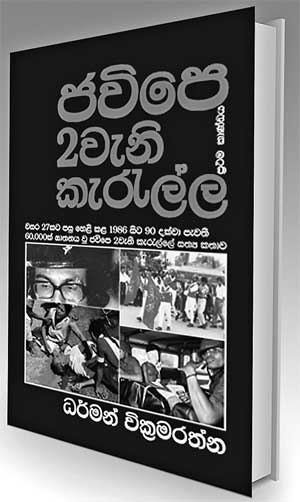

Dharman Wickremaratne’s book ‘The JVP’s 2nd rebellion’ (Javipe Deveni Kerella) is therefore an historically important work which fills a void. Running to almost 900 pages, it narrates the story of the Janatha Vimukthi Peremuna (JVP), its leader Rohana Wijeweera and key members from 1971 to the second rebellion, from its humble beginnings on May 14, 1965, to the final blood-soaked chapters that followed the killing of Wijeweera in Colombo, in November 1989. In putting together the big picture, Dharman Wickremaratne traces the history of Sri Lanka’s labour agitation and trade union action going back several decades, such as the abortive July 1980 strike. This is important since the deep social malaise which gave birth and impetus to the JVP did not spring from thin air. While he doesn’t attempt historical analysis in an academic sense, the author has researched the roots of these two rebellions and the result is a highly readable factual history of this country’s volatile politics from the 1970s onwards. According to independent estimates, over 72,000 lives were lost during the two rebellions, the vast majority of these during the second. While it is doubtful if the country’s leaders learned any lasting lessons from this mayhem, or if any meaningful reforms were brought about as a result, such a dark chapter in Sri Lankan history cannot go unrecorded. More than a gruesome record of the torture chambers is required, and Dharman Wickremaratne has put together here with consummate skill a narrative history of the 2nd JVP rebellion, with the story of its leader and the first rebellion included as a vital backdrop.

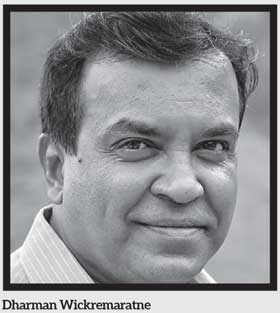

This is as close as we are likely to get to what actually happened at the time, because  classified records do not exist (if they do by chance, no one knows where they are and the public has no access). By 1989, the police, the army and the paramilitary groups loyal to the government were given a carte blanche to crush the rebellion by whatever means available. This meant wholesale slaughter on an unprecedented scale and they obviously did not want to leave records. Any writer attempting a history of this mayhem faces a Herculean task because he or she would need to rely on survivors’ and eye-witness accounts and newspaper archival material, which are not always accurate. Dharman Wickremaratne was a 23-year-old reporter for the Sinhala newspaper Divaina in 1987. He covered the rebellion from its start to finish, had extensive contacts at all levels with both sides, and took considerable personal risks. As the author states in his foreword, he was on a flight to Germany in 1990, when it was recalled after take off and he was arrested and later questioned by the CID about his contacts.

classified records do not exist (if they do by chance, no one knows where they are and the public has no access). By 1989, the police, the army and the paramilitary groups loyal to the government were given a carte blanche to crush the rebellion by whatever means available. This meant wholesale slaughter on an unprecedented scale and they obviously did not want to leave records. Any writer attempting a history of this mayhem faces a Herculean task because he or she would need to rely on survivors’ and eye-witness accounts and newspaper archival material, which are not always accurate. Dharman Wickremaratne was a 23-year-old reporter for the Sinhala newspaper Divaina in 1987. He covered the rebellion from its start to finish, had extensive contacts at all levels with both sides, and took considerable personal risks. As the author states in his foreword, he was on a flight to Germany in 1990, when it was recalled after take off and he was arrested and later questioned by the CID about his contacts.

Undeterred, he continued to collect documents, data, letters, photographs and diaries over the years, and mentions two persons who agreed to safeguard this vast collection, which is the source of material for this book. He emphasizes that the story doesn’t end with it, nor does he claim that it’s complete. But it is ambitious in scope and offers in a logical and chronological order, the key events of a very violent and bleak period.

The author does not attempt socio-analysis or psychological profiles of key protagonists. Rather, he gives an outline of the historical factors and socio-economic forces which gave birth to the JVP, which was a radical but legally established political party as well as an underground political and military movement, according to the dictates of time and place. He concentrates on a detailed history of events and participants, major as well as minor, with an amazing attention to detail. Crammed into 74 chapters and lavishly illustrated with hundreds of black and white photographs of places and people (including the many victims of the JVP and the DJV, its shadowy military wing during the second rebellion), the narration becomes almost a day-by-day account of events – meetings, protests, key decisions, armed attacks, assassinations and abductions. It’s a factual thriller based on real life events.

Unlike many of the survivor-turned journalists who concentrated on the gory details of torture in their newspaper articles, Wickremaratne does not descend into the ‘pornography of violence.’ He deals more with the causes of that gore, the monumental decisions, as well as mistakes made by Wijeweera, his central committee and their counterparts in the governments and security apparatus.

He does this in a logical, chronological order and discusses the role played by influential organizations such as the university’s independent students’ union and its third president Daya Pathirana (abducted and killed in 1986 by the JVP) and the Mavubima Surakime Vyaparaya led by the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) but manipulated by the JVP.

The narrative includes many, now-largely forgotten episodes, such as the abortive pact between the J.R. Jayewardene government and the JVP, signed on May 9, 1989 with minister Lalith Athulathmudali as state representative and the JVP’s Upatissa Gamanayake, with Fr. Tissa Balasuriya as one of two witnesses, whereby the JVP agreed to disarm and enter the democratic process (it barely lasted a week).

The book makes it clear that the JVP was supremely able to harness the nationalist feeling (mainly Sinhala Buddhist but sometimes extending beyond), which became a rallying point for pent-up fury against then president J.R. Jayewardene’s high-handed and authoritarian manner. This reached a boiling point when he signed the Indo-Sri Lanka accord with Indian PM Rajiv Gandhi in 1987. Just as the July 1983-anti Tamil riots fuelled the LTTE, this accord and ensuing anti-government riots transformed the JVP into a highly potent alternative force fighting to topple the state, at least in the eyes of those who feared international invention and Indian meddling in Sri Lanka’s volatile politics. The regime’s mix of virulent Sinhala nationalism and pro-Western diplomacy was countered squarely now by the JVP’s xenophobia.

Many examples can be given for the author’s attention to detail. For example, when describing the attack on Rajiv Gandhi on July 30, 1987 by naval rating Vijitha Rohana Wijemuni, he mentions the name of the only photographer able to capture the image (Lake House photographer Sena Widanagama) and how the decision to publish this picture only in their city editions was taken by Lake House. The author then describes in detail the family background of Wijemuni and the ensuing trial. Many such examples are found throughout the book.

The period is full of many such absorbing episodes, including the grenade attack inside the parliament in August 1987. Employee Ajith Kumara, accused of the attack, was later absolved of all charges after a trial. These facts are known. Less known perhaps is the fact that his wife and son (born in 1986) both disappeared after his arrest, and the author states that both were killed. He doesn’t say by whom. The story of the Deshapremi Janatha Vyaparaya, the JVP’s shadowy and brutal military wing, runs parallel. It was commanded by Saman Piyasiri Fernando, better known by his nom de guerre of Keerthi Wijebahu, a name  that struck terror in the hearts of millions. According to the statistics given by the author, the DJV murdered 1,783 UNP members, 485 state officials and employees, 202 soldiers, 187 university and school students, 92 members of policemen’s families, 70 members of armed forces members’ families, 52 school principals, 41 Buddhist monks, 27 trade union activists, 18 estate superintendents, 9 journalists and artists, 7 lawyers, 6 leading businessmen, 1 Catholic priest, 200 SLFP members, 141 members of the Mahajana Pakshaya, 43 members of the Communist Party and many more.

that struck terror in the hearts of millions. According to the statistics given by the author, the DJV murdered 1,783 UNP members, 485 state officials and employees, 202 soldiers, 187 university and school students, 92 members of policemen’s families, 70 members of armed forces members’ families, 52 school principals, 41 Buddhist monks, 27 trade union activists, 18 estate superintendents, 9 journalists and artists, 7 lawyers, 6 leading businessmen, 1 Catholic priest, 200 SLFP members, 141 members of the Mahajana Pakshaya, 43 members of the Communist Party and many more.

The DJV punished those who dared disobey its dictates during the June 1989 SLTB bus strike ruthlessly. It started locally at Badulla but was soon orchestrated brilliantly by the JVP island-wide to cripple the entire country, with the railways and the private bus operators being forced to join. 137 SLTB employees who dared go to work were killed, and one driver’s hands were hacked off and placed on the steering wheel of his bus as punishment.

With such senseless murder and brutality, by 1989 the JVP was self-destructing. Its terror was such that during the 1988 presidential election, not a single vote was cast at 270 polling centres and 15 opposition candidates for the 1989 general election were killed. The July 1989 JVP central committee decision to end its ‘cohabitation’ with the SLFP and attack it too was another major blunder.

But it’s the August 1989 JVP order given to all armed forces members to quit or face reprisals which delivered the final coup de grace. The Ops Combine was formed under Maj. Gen. Cecil Waidyaratne, with another special ops unit under Col. Janaka Perera, and police SSP Premadasa Udugampola was given a free hand to fight the JVP and the DJV. The result was a bloodbath which wiped out almost the entire underground leadership within a matter of months. Despite its virulent nationalism, the JVP maintained contacts with a number of Tamil separatist groups and these details too are given along with a sketchy history of the Tamil armed struggle. Though the JVP was overwhelmingly Sinhalese, it had a few very active minority members too. One was a brilliant and popular Tamil student leader called Ranjithan Gunaratnam, who became the JVP leader for Western and Sabaragamuwa provinces. He was arrested in December 1989 and killed in January 1990. Among its few Muslim activists, engineering undergraduate S.M. Nizmi was one. When he was arrested in January 1990, he was a JVP central committee member and was killed soon after.

Many brilliant and capable people from both sides perished. What was achieved in the end after such enormous sacrifice? The author does not proceed to answer such questions. He sees his task as one of documenting in a coherent manner a mass of detail and reportage of a very murky era, and in this he has succeeded quite well. Has he been impartial? But total impartiality would be impossible in such an undertaking. Lord Russel of Liverpool, one of the chief legal advisers during the war crimes trials at Nuremberg and Tokyo after WWII, wrote two outstanding books about Axis war crimes – The Scourge of the Swastika and the Knights of Bushido. He represented the Allied side and was a firm liberal. But this did not make him exaggerate or invent. That’s the most important thing. Similarly, one feels that author Wickremaratne has worked within the bounds of historical truth and decency. Because of the very nature of its subject matter, some parts of the book are bound to be controversial. But it’s hard to think of anyone else better placed to undertake such a monumental task and he doesn’t consider it complete. The second part of the book will resurrect more of this unwritten history.

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul

A recent post on social media revealed that three purple-faced langurs near t