Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-25 09:17:00

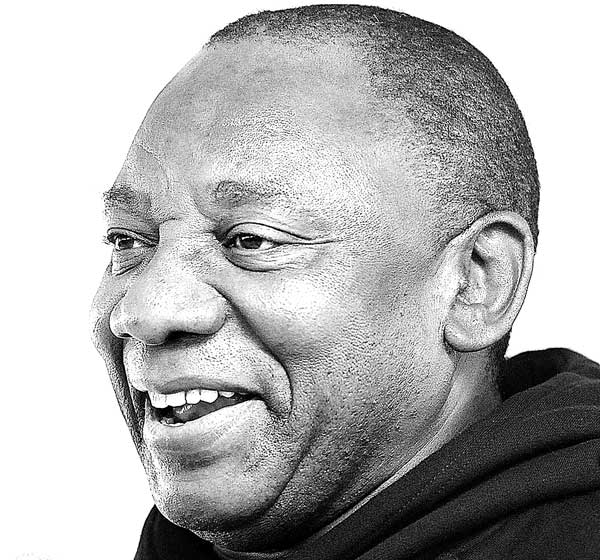

.jpg) In his first public comments on his role in Sri Lanka since being appointed as President Jacob Zuma’s special envoy to Sri Lanka, Cyril Ramaphosa has said that South Africa’s post-Apartheid success in building a new nation that embraced democracy and human rights had endeared the country to many others around the world, including Sri Lanka. “Our country used to be the pariah of the world, and today we are the darling of the world... Some of those that have come to respect us greatly are countries like Sri Lanka,” he said in a speech recently at Mount Edgecombe, KwaZulu Natal in South Africa. He went further to say, “We are truly honoured to be chosen among many countries to go and make this type of contribution to the people of Sri Lanka,” he said. “We have a wonderful story to tell, and it is this wonderful story that the Sri Lankans see.”

In his first public comments on his role in Sri Lanka since being appointed as President Jacob Zuma’s special envoy to Sri Lanka, Cyril Ramaphosa has said that South Africa’s post-Apartheid success in building a new nation that embraced democracy and human rights had endeared the country to many others around the world, including Sri Lanka. “Our country used to be the pariah of the world, and today we are the darling of the world... Some of those that have come to respect us greatly are countries like Sri Lanka,” he said in a speech recently at Mount Edgecombe, KwaZulu Natal in South Africa. He went further to say, “We are truly honoured to be chosen among many countries to go and make this type of contribution to the people of Sri Lanka,” he said. “We have a wonderful story to tell, and it is this wonderful story that the Sri Lankans see.”

(1)(18).jpg)

(1)(18).jpg)

(1)(18).jpg)

(1)(18).jpg)

(1)(18).jpg)

(1)(18).jpg)

(1)(18).jpg)

(1)(18).jpg)

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

US authorities are currently reviewing the manifest of every cargo aboard MV

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul