Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-20 09:22:00

BY Anarkalee Perera

BY Anarkalee Perera

There is broad consensus that women’s empowerment underpins the success of the new 2030 Agenda for Development (also known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)). While gender equality itself constitutes one of the 17 development goals (Goal 5), it is widely acknowledged that the empowerment of women and girls is an important prerequisite for the realisation of all other goals, including the reduction of poverty (Goal 1), inequality (Goal 10) and the promotion of inclusive and sustainable economic growth through decent work for all (Goal 8).

This new development agenda also has an important focus on unpaid care work. Accordingly, target 5.4 of the SDGs calls upon nations to ‘recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family.’

Unpaid care work – which refers to all unpaid services provided within a household for its members, including care of persons, domestic chores and voluntary community work – is an area that has long been neglected by economists. Traditionally, this work was considered to be ‘women’s work’, performed in the ‘private sphere’, for the benefit of ‘loved ones’. The gendered, private and voluntary nature of this work formed the basis for its invisibility in the economy and led to its sustained exclusion from national income accounts and macroeconomic statistics around the world.

The inclusion of unpaid care work as a target in the 2030 Development Agenda, therefore, marks an important watershed in the recognition and valuation of this type of work. It has shed light on the immense economic value of unpaid care work and more significantly, prompted an important conversation on women’s contributions to the global economy.

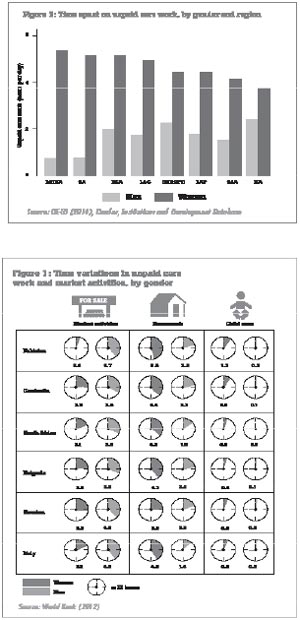

Globally, women bear disproportionate responsibility for unpaid care work. This is largely because the prevailing gender norms define domestic work as a female prerogative. Studies reveal that over 75 percent of the world’s total unpaid care work is done by women. In South Asia and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), this share is much higher, with women undertaking nearly 80-90 percent of total care and domestic work in the economy. Time-use data from across the world support these findings: statistics from six different countries – with varying income levels and socio-economic structures — reveal that women everywhere devote one to three more hours each day to housework than men; two to 10 times the amount of time a day to care (for children, elderly and the sick) and one to four hours less a day to market activities (Figure 1). Notwithstanding minor differences, it is clear that this trend holds true in almost every region of the world (Figure 2).

The gendered distribution of unpaid care work has important implications for the well-being of individuals and households, as well as for the economic development in a country. It has a direct effect on labour market outcomes, particularly with respect to women’s labour force participation, wage distribution and job quality. It also has direct, negative impacts on the health and well-being of women. It is in light of this revelation that Diane Elson, Professor of Economics at the University of Essex, developed the 3R Framework, which calls on countries to Recognize, Reduce and Redistribute unpaid care work in the economy. This framework has now been widely adopted by the international development community, including the United Nations and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, as an effective strategy to empower women as economic actors. However, many countries continue to exclude unpaid care work from their policy agendas.

Why should Sri Lanka recognize, reduce and redistribute unpaid care work?

Sri Lanka too remains blind to all but paid, visible forms of women’s economic contribution. This has led to significant gaps in economic policymaking and governance. Outlined below are some of the reasons why Sri Lanka should address the unequal distribution of unpaid care and domestic work in the economy.

Increase female labour force participation: The gender gap in unpaid care work has significant implications for women’s ability to actively participate in the labour force. Unpaid care work shapes the duration, quality and type of paid work that women can to undertake. For every hour that a woman spends on domestic chores, she foregoes the opportunity to engage in the labour market or to invest in educational activities. In many respects, unpaid care work is the missing link that influences gender gaps in labour outcomes. Therefore, in countries like Sri Lanka, where female labour force participation is low, redistribution of care work could help to increase women’s participation in the labour force.

Increase women’s financial independence and access to social protection: The opportunity cost associated with unpaid care work is the foregone potential to earn an income, to save and to accumulate assets. Statistics reveal that in countries where women spend twice as much time as men on unpaid care work, they earn 65 percent of what their male counterparts earn for the same job. Furthermore, women who forgo gainful employment or spend intermittent periods of time in the labour force, lose access to vital social protection (such as pensions) in the long run. This, in turn, places women at a much higher risk of poverty at old age.

Increase returns on education and reduce wage-inequalities: The gendered nature of the relationship between unpaid care work and paid work has also led to higher wage differentials in the labour market. Studies reveal that the gender wage gap is much larger among parents than among men and women who have no children. In the United States, childless women (including married and unmarried) earn 93 cents on a childless man’s dollar. On the other hand, married mothers with at least one child under age 18 earn 76 cents on a married father’s dollar. In addition, research has shown that the burden of unpaid care work has also led to lower returns on education for women. In Sri Lanka, female graduates outnumber male graduates at the tertiary level, but constitute only 35.9 percent of the labour force. Thus, the redistribution of care responsibilities and domestic chores could result in greater returns on education in the country.

Increase women’s quality of life: Unequal care responsibilities contribute to time-poverty, limited mobility and poor well-being among women. A robust body of evidence reveals that care and domestic responsibilities render women ‘time-poor’. This is because responsibility for care work leaves only a few hours for engaging in leisure activities that improve health and well-being. This is particularly significant for women who are engaged in the labour market full-time. Despite the fact that women spend as much time as their male partners in paid work, they are required to fulfil domestic responsibilities. As a result, women ‘work’ much longer hours than men. In fact, a recent study estimated that women perform an average of four years’ more worth of work than men – or an extra month’s worth of work per year – in order to balance their commitments to both paid and unpaid care work. Addressing the gender division of unpaid care work is therefore vital to improving women’s quality of life and standard of living.

Conclusion and recommendations

While anecdotal evidence may highlight the inherent gender disparities in unpaid care and domestic work in Sri Lanka, the country lacks comprehensive data to inform policymaking. At present, Sri Lanka does not conduct any nationally representative time-use surveys, which could effectively capture the distribution of care work between men and women in the country. Collection and dissemination of data is vital to informing policies that would reduce the burden of care work on women and redistribute domestic responsibilities among men and other institutional actors in the economy.

Sri Lanka should further consider the urgency of improving policy readiness to achieve the SDGs. If the country hopes to stay on track, it must work immediately to address the issue of unpaid care work – a target that is indispensable to the attainment of Goal 5 of the SDGs.

(Anarakalee Perera was a Research Assistant attached to the Poverty and Social Welfare Unit of the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS). Her research interests include poverty and development policy, with a focus on public-private partnerships (PPP), information and communications technology (ICT) and gender policy. She holds a BA (cum laude) in International Affairs and Economics with a certificate in Development Studies from Mount Holyoke College, USA. She can be reached at

anarkalee@ips.lk)

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul

A recent post on social media revealed that three purple-faced langurs near t