Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-19 14:00:00

he end of the war anniversary this month is once again polarizing the country. The losses are again being counted along ethnic lines, reinforcing notions of “war heroes” and “martyrs”. Remembering the war and the dead in this manner is providing few lessons and avenues towards seeking a peaceful and just future.

he end of the war anniversary this month is once again polarizing the country. The losses are again being counted along ethnic lines, reinforcing notions of “war heroes” and “martyrs”. Remembering the war and the dead in this manner is providing few lessons and avenues towards seeking a peaceful and just future.

With the changing political dispensation in the South this year, a new constitution to address the issues that underlie the conflict are no longer in sight. In side stepping the issue of a political  settlement, the doors are widening again for majoritarianism and jingoism in the South.

settlement, the doors are widening again for majoritarianism and jingoism in the South.

In the North, the Chief Minister and his speech at the remembrance in Mullivaikkal last week have reiterated the problematic discourse of genocide. This narrative of genocide denies the history of ethnic co-existence in this country, including during war-time, and seeks to construct an exclusionary and separatist future.

Among the many issues we should have addressed over the last many years, here I touch on the issue of demilitarization. Indeed, we are yet to have a national debate on the role of the military after the end of the war.

" Sadly, funds and finances are far more willingly allocated for war-making than reintegration

and reconstruction "

While any country after a war should downsize its military, demilitarization is much more than that. In any event, reducing military numbers necessarily involves reintegrating the men and women in uniform with opportunities for civilian employment. But such opportunities for employment remain limited. The same goes for ex-combatants, including from the LTTE, who continue to be ostracised from local employment.

The families of the dead and disappeared have lost breadwinners. Their trauma of loss is amplified as many of them struggle to eke out a living. In this context, national efforts to rebuild their economic life, through employment and income generation have been lacking. If one takes the national budget, defence expenditure still tops the list. Why is it that we have not thought about financing programmes with a part of those funds to reintegrate soldiers through education and civilian employment? Meanwhile, not even a minuscule fraction of the Tamil diaspora funding that came during the war has been channelled for post-war development of the North and the East. Sadly, funds and finances are far more willingly allocated for war-making than reintegration

and reconstruction.

As we learned all too well during the years after 2009, militarization can take many forms, including the usurping of civilian institutions by the military. The merging of the Urban Development Authority (UDA) with the Defence Ministry characterized the institutionalization of militarized urbanization under the Rajapaksa Government. While the UDA was separated after regime change, military funded farms and pre-schools continue in the North to this day.

The security sector creeping into civilian institutions is not confined to the North. In recent weeks, steps have been taken to expand the role of the Kotelawala Defence University (KDU) in the higher education sector. Pushed through or not, these efforts to bring urban, rural and educational institutions under defence are worrying signs of a militarized mind-set.

As in many other parts of the world, militarization in Sri Lanka is very much linked to muscular nationalism. Post-war politics continue in that nationalist vein. There has been little self-criticism and reflection about how nationalist politics polarizes and oppresses, particularly women while claiming to protect them, and pushes generations of youth towards war and destruction. In the post-war years, nationalist mobilizations in tandem with end of war remembrances and opportunistic electioneering, have kept communities insecure.

"Remembering war-time loss and destruction must go hand in hand with calls for material changes; from demilitarizing institutions to setting post-war development priorities and initiatives"

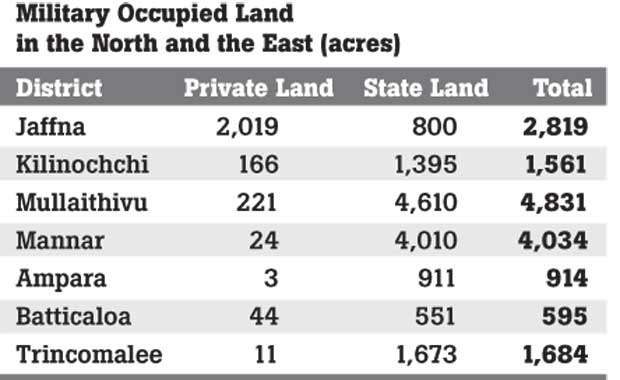

A recent report in The Hindu (18 May 2018) included data on the spread of military occupied lands in the North and the East, and is reproduced here. Much of the discussion on demilitarization, in the North in particular, has been about military occupation. Despite the swathes of land still under the military, significant areas have been released in recent times; including the Myliddy Fisheries Harbour in 2017 and 683 acres in Palaly last month. Furthermore, people’s struggles have been crucial for demanding land releases. Last month, the displaced people of Iranatheevu, an island off Kilinochchi occupied by the Navy for decades, took it upon themselves to return and reclaim their own.

The government needs to release more military occupied land, particularly in Jaffna where land is scarce. In Jaffna, close to 15,000 families, ten percent of the households in the District, are absolutely landless. However, even the release of military occupied lands is unlikely to change their situation. Indeed, these landless families displaced multiple times during the war are the most deprived in northern society, but they do not even qualify for the post-war housing grants by the Government.

The very actors who strongly advocate for the release of military occupied land, rarely talk about landlessness in the post-war North. Ironically, Tamil nationalists raise concerns about the presence of the military but ignore the predicament of the landless and the marginalized, the very people who were cannon fodder during the war. In the South and the North, territorialism and militarism are occupying the minds as well.

Remembering war-time loss and destruction must go hand in hand with calls for material changes; from demilitarizing institutions to setting post-war development priorities and initiatives. However, in these fraught times of nationalist resurgence, we have to emphasize changing the mind-set in the country towards demilitarization.

Tamils in the North remember their lost kin

Tamils in the North remember their lost kin

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul

A recent post on social media revealed that three purple-faced langurs near t