Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-23 22:35:00

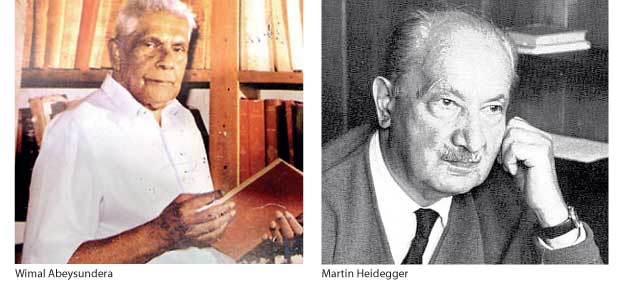

Wimal Abeysundera is closely associated with the Colombo School of Poets that had a profound impact on Sinhala poetry mainly during the period from 1940 to 1970.There was much poetry written during this period. Admittedly, much of the poetry written during this period is mediocre. However there were poets like Wimalaratna Kumaragama and Sagara Palansuriya who wrote poetry worthy of serious consideration. Wimal Abeysundera distinguished himself from most other Colombo poets by his deep knowledge of Sinhala, Pali, Sanskrit and his intimate acquaintance with Buddhist thought.

Wimal Abeysundera is closely associated with the Colombo School of Poets that had a profound impact on Sinhala poetry mainly during the period from 1940 to 1970.There was much poetry written during this period. Admittedly, much of the poetry written during this period is mediocre. However there were poets like Wimalaratna Kumaragama and Sagara Palansuriya who wrote poetry worthy of serious consideration. Wimal Abeysundera distinguished himself from most other Colombo poets by his deep knowledge of Sinhala, Pali, Sanskrit and his intimate acquaintance with Buddhist thought.

One feature that marks Wimal Abeusundera’s poetry is its display of a Buddhist consciousness. It inflects his themes, tropes, and vision. When we examine his poetry we see that it is closely related to Buddhist thought and Buddhist sensibility. It is evident that in his poetry he has been inspired by traditional Buddhist narratives. Among his interesting poetic compositions are retellings of traditional Buddhist narratives. He has also recreated vividly various sites of Buddhist worship which generate in the reader a sense of awe and reverence. In addition Abeysundera has sought to recreate the power and glory of diverse Buddhist personalities that have a relevance to the generality of readers. Most Importantly, Abeysundera was keen on displaying the continuing relevance of Buddhist understandings, values, norms and outlook for contemporary society.

Heidegger subscribed to an extreme form of this constitutive theory of language. He said that it isn’t man that speaks language, but language that speaks through man. He asserted that, “We don’t merely speak the language. We have already listened to language. What do we hear?

In order to understand the true significance of Abeysundera’s poetry we need to pay closer attention to Buddhist values. As a consequence of the forces of modernization and globalization the face of society is changing rapidly. This has profound consequences on the values and norms that guide our lives.

Abeysundera was clearly perturbed by the inimical and destructive forces unleashed by the consumer society. The imperative of the consumer is everywhere and he views with alarm the corrosive effect it has on the day to day lives of people. In order to counteract these unhealthy forces, Abeysundera, through his poetry, has sought to underscore the importance and relevance of Buddhist values. This indeed constitutes an important facet of his poetry.

In addition to his poetry, Abeysundera has written a number of important critical essays that deal with the discourse of poetry as well as the distinguishing features of the poetry produced by the Colombo School. Some of these critical essays offer us many significant insights in to the ambitions, preferred pathways, agendas and visions of this group of poets. He does so based on his intimate experiences with this group of poets.

As I stated earlier, a significant feature that serves to differentiate Abeysundera from many other poets belonging to the Colombo School is the vast linguistic resources he had at is command. His fluency in Sinhala, Pali and Sanskrit stood him in good stead. This verbal facility is intimately linked to what I think is an important concept on poetic discourse, namely, the distinct ability to listen to language. The ability to listen to language sensitively and purposefully, it seems to me, is a mark of a good poet.

The phrase listening to language was put into wider circulation by the German philosopher Martin Heidegger. He is, to be sure, a controversial figure. His flirtation with Nazism for a short period of time permanently tarnished his reputation. At the same time, most esteemed philosophers regard him very highly. Some even claim that he was the most original thinker of the twentieth century. He had important things to say about a variety of topics including language and poetry.

As I stated earlier, a significant feature that serves to differentiate Abeysundera from many other poets belonging to the Colombo School is the vast linguistic resources he had at is command. His fluency in Sinhala, Pali and Sanskrit stood him in good stead

To my mind, Heidegger’s approach to language merits very close attention, especially if those of us are deeply interested in poetry. His favourite poet was the German poet Holderlin. He had very many interesting observations to make about Holderlin’s poetry and the intricate ways in which language works in and through his poems. It seems that we in Sri Lanka haven’t paid adequate attention to Heidegger’s specific views on language and poetry.

As I stated earlier Heidegger was responsible for putting into wider circulation the idea of listening to language and its compelling significance in order to understand the true important of this idea. Let us first explore in broad outline martin Heidegger’s approach to language or as he would prefer to say path to language. As he sees it, there are two broad approaches to language, instrumental and constitutive. The first seeks to encircle the fact that language is an instrument of communication, that we exchange ideas, thoughts and opinions that are re-formed through the medium of language.

Those who subscribe to this view believe that language can be understood within a picture of life. This means that language arises from within this framework, but the framework itself operated independently of, or prior to, language. The constitutive approach, on the other hand, states emphatically that language is no mere instrument of thought, but rather that it is constitutive of thought. Here language becomes pivotal to thought formation. Heidegger subscribed to an extreme form of this constitutive theory of language.

He said that it isn’t man that speaks language, but language that speaks through man. He asserted that, “We don’t merely speak the language. We have already listened to language. What do we hear? We hear language speaking. His central trope of language was that of a house of being. This encapsulates ably the essence of his thinking on language. He was of the opinion that it wasn’t possible for us to step outside language, because human beings was inescapably within language already. Heidegger isn’t interested in the surface phenomena of language, the communication that transpires within a context that is already fashioned, but rather in the manner in which language makes that very context possible. He once remarked that, ‘only when there is language is there a world.”

In order to understand Heidegger’s constitutive approach to language, we need to pay close attention to the way he commented upon admiringly on Holderlin’s poetry. The language of poetry, for him, was of paramount importance. The significance of poetry for Heidegger resides in the fact that it reproduces the original moment before speech. This original moment is marked by our willingness to allow language to speak to us. In an essay titled language in the poem, which deals with the poetry of Georg Traki, Heidegger remarked that, ‘the dialogue of thinking with poetry aims to call for the nature of language, so that mortals may learn to live with language again.’ What he is stating here is that in the poem language should be regarded as an opening to language, and it is only by listening to language that we can situate ourselves in the very existence of the world.

One feature that marks Wimal Abeusundera’s poetry is its display of a Buddhist consciousness. It inflects his themes, tropes, and vision.

What this discussion about Heidegger’s attitude to language and his vision of poetry tells us about our own endeavours to study Sinhala poetry in terms of the uniqueness if a given language and its intersections of phonetic and syntactic structured are the following; language should be seen as constitutive of meaning, nothing happens outside language, we operate within specified linguistic universes, the uniqueness of languages and their respective and informing acoustic patterns merit very close study. These observations have a pointed relevance to Abeysundera’s poetry. He was sensitive to languages; he listened to language much more intently than most other Colombo school poets.

Distinguished English critic Graham Hough, in his book on essays, makes the point that each language, whether it be English or German or Chinese, has its own distinctive phonetic and semantic features which demand close attention.

These features could constitute a useful basis for the productive exploration into the complexities of the poetic experience and the nature of poetry. Similarly George Steiner, in many of his critical essays, has drawn attention to the lexical, syntactic, phonetic features of different languages and what this means to the understanding of poetry.

As I stated earlier Heidegger was responsible for putting into wider circulation the idea of listening to language and its compelling significance in order to understand the true important of this idea.

This linguistic uniqueness, in my judgment, can become a useful point of departure in investigating the defining and constitutive features of poetry. Perceptive poets are sustained by the conviction that recognition of the uniqueness of his or her linguistic terrain is a prelude to poetic achievement. Abeysundera was deeply aware of this fact.

What I have sought to achieve in this short essay, then, is to focus on the constitutive theory of language and the imperative need to listen to language as a way of illuminating an important facet of Abeysundera’s poetry. Poems contained in a book, such as the Manasa, illustrates this point forcefully. This is all the more important in view of the fact that much of the poetry written today displays a conspicuous lack of this desire to listen to language intently, to hear language speaking to us.

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul

A recent post on social media revealed that three purple-faced langurs near t