Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-25 00:00:00

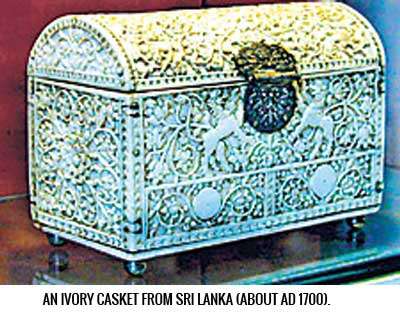

The British were smart, all things considered. They didn’t just destroy our cultural artefacts like the Portuguese and Dutch did, they took them away and then turned them into exhibits. I know enough and more people who claim that this is (somehow) proof of their benevolence and that those artefacts are better protected in London  than in Colombo. I won’t argue, especially because we don’t have a squeaky clean record when it comes to preserving our own treasures, but I will say this: preserved or not, those treasures are still ours. And preserved or not, it doesn’t erase the fact that their forced eviction from the home country constituted theft. Newspaper editorials which shout whenever Sri Lankans, especially Sinhalese Buddhists, “allegedly” vandalise cultural sites belonging to other ethnicities seem to go dumb over this hard reality.

than in Colombo. I won’t argue, especially because we don’t have a squeaky clean record when it comes to preserving our own treasures, but I will say this: preserved or not, those treasures are still ours. And preserved or not, it doesn’t erase the fact that their forced eviction from the home country constituted theft. Newspaper editorials which shout whenever Sri Lankans, especially Sinhalese Buddhists, “allegedly” vandalise cultural sites belonging to other ethnicities seem to go dumb over this hard reality.

I was thinking of this business of preserving and exhibiting cultural artefacts looted from other countries some time back. I was amazed at the rate at which this industry has grown over the years. Were it not for that industry, Keats may never have written his better known odes (like “On a Grecian Urn”) and for all we know the world would have forgotten that there was such a thing as a Koh-I-Noor.

This is not to suggest that the British were doing us any favours by taking those treasures away. Let’s not forget that the British Museum was run to empower the “other side” of colonialism, and that over the decades it became the repository of orientalism, which as everyone (even the orientalists) know is a polite term for cultural condescension. Still, a few charitable thoughts are, I feel, called for.

The British Museum is the world’s oldest national public museum. It is not run to yield a profit. It is not run as a corporation. Unlike the Colombo Museum, which charges fees ranging from Rs.30 (for locals) to Rs.500 (for foreigners), it is, barring the occasional exhibition, free. Operated and managed as a non-departmental public body (a public body not attached to a government department), it is financed by donations, legacies, and trading activities including but not limited to onsite retailing, corporate hire, sponsorship incomes, and of course catering. From 2001 to 2018, a space of more than 15 years, grants from the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport have oscillated from 35 to 40 million pounds annually, a figure which has survived the austerity cuts of the David Cameron regime. The British clearly love their artefacts, even if they were looted from the colonies, and they clearly are committed to the preservation of them.

So clearly, while museums in general have become a profit-driven industry, the British Museum has not become a business by any stretch of the imagination. There are no entrance fees, except for the occasional donation-requirement, and apart from a few items here and there the cost of a visit is virtually zero. And yet, even with this absence of a profit motive, the British Museum is thriving. It has a firm governance structure (with 25 trustees), the largest online database of objects from any museum collection (more than two million object entries). In 2013, it attracted 20% more visitors than it did in 2012, an impressive rise considering that these were years of heavy funding cuts. The British love their history, even if their history is smudged with ours, and their connoisseurship deserves more than just a customary clap.

Sri Lanka, on the other hand, is not so fortunate. The Colombo Museum has entrance fees, a ready source of income if ever there was one, given that it attracts a sizeable crowd even today, but then as one commentator put it in an article months ago, we still have not been able to transform it into more than just a series of exotic exhibits. Put simply, we exhibit our history the same way we teach it to our children: a set of dates, events, and carefully marked items to look at and note down.

And it’s not just the Colombo Museum. Sri Lanka presently has three other national museums, in Kandy, Ratnapura, and Galle. Then there are the other subsidiary sites, like the Folk Museum in Anuradhapura and the Independence Memorial Museum in Colombo. They are all run by one government department or the other, including the Department of Archaeological Survey, which oversees 27 such museums. All these departments, moreover, centre around one public authority: the Central Cultural Fund (CCF), established in 1981 to preserve important sites along the Cultural Triangle. For the purpose of comparison, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport took 16 more years to be established.

And yet, even with all these bureaucratic safeguards, can one really say that we have opened our cultural artefacts to our own people, let alone outsiders? Isn’t it an irony that while museums in the developed world have been transformed successfully from colonialist enterprises to contemporary institutions, our main public museum remains a pale replica of those colonial era projects? The purpose of such places is to offer the discerning observer a sense of order in the exhibiting and unveiling of history. Is such a purpose being met here? The problem gets even more complicated when we consider the attitude towards our own history that has been nurtured among us. We spend 10 or 11 years memorising dates and events without being able to identify or make connections between one era and another. We think that by remembering those dates and events, we can remember history. But “history,” as scholars and amateurs alike will tell you, cannot be boiled down to what can be remembered this way. “History” is made up of certain cosmetics, and it is those cosmetics which museums must endeavour to reveal and, in a manner of speaking, undress for us.

There are myths associated with historical events and there are links between certain disparate historical phenomena. Would there have been a massive irrigation network and hydraulic civilisation in Sri Lanka without the advent of Buddhism, to give just one example? My guess is no, but textbooks hardly delve into why this may be so. To understand what these connections are, you need to go beyond the classroom. And museums are an integral part of that beyond-the-classroom experience. It is an experience that today has become limited to the occasional school visit.

Professor K.M. de Silva tried over several decades in his ‘History of Sri Lanka’ to chart the trajectory of our civilisation through those aforementioned links. As of the latest edition, the book tries admirably to sustain our interest in our past, and for this reason it is the definitive work on local history in English. Not that there haven’t been other endeavours of course, but the difference with Professor de Silva’s work is that it offers an entire spectacle, a combination of close-ups and long shots that provides an accurate, if not multifarious, perspective of our heritage.

Apart from certain biases and prejudices which crop up (in particular, his view of Zheng He, the Chinese maritime explorer, as a crude imperialist who sought to steal the Dantha Dathuwa, when the reasons for his invasion of Kotte and “abduction” of Vijayabahu VI are much more complex than that), de Silva’s book treats history as a material reality with spiritual undercurrents (which means that even that most hailed of all irrigation equipment, the bisokotuwa, was the definitive product of a civilisation run along Buddhist lines), which I think is a far superior approach to the subject than the series of conquests and defeats we are forced to vomit at the exam hall every year.

It is said that we have become indifferent to culture. But what is culture? Is it, as the orientalists will have you imagine, a set of unique exotic identifiers that demarcate a non-Western civilisation? Or is it, as the Marxists will have you believe, one of many superstructures through which the real history, the oppression of the underprivileged, is erased if not whitewashed?

I believe it is neither. “Culture” as is understood in the Western sense is a product or consequence (or baby) of the Industrial Revolution, which as Ananda Coomaraswamy has pointed out managed to differentiate between objects of mass consumption and objects of artistic edification. Coomaraswamy saw this as a debasement of human values. I would agree. In that regard, culture has become an esoteric enterprise.

It was not always like this, though, since in the early days, there was nothing that could actually be detached from common experience and exhibited in the name of “art” or “history.” On the contrary, it was the seamless fusion of the material and the metaphysical which produced the “culture” our ancestors venerated ages ago. The more we understand this, the more we will realise where we are going wrong, and where the British Museum curators are not. But will it be too late by the time we do realise? I sincerely hope not.

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

US authorities are currently reviewing the manifest of every cargo aboard MV

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul