17 Sep 2019 - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

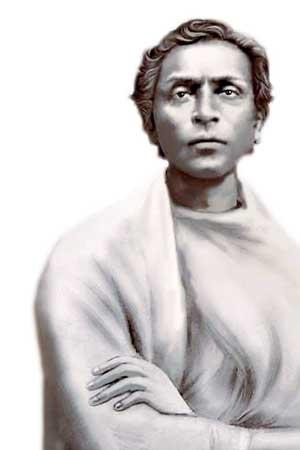

Mary Foster Robinson, a Hawaiian lady was the single largest benefactress of the Anagarika Dharmapala, Founder of the Maha Bodhi Society, whose 155th birth anniversary falls today (September 17).

Mary Foster Robinson, a Hawaiian lady was the single largest benefactress of the Anagarika Dharmapala, Founder of the Maha Bodhi Society, whose 155th birth anniversary falls today (September 17).

Her financial assistance to win back Buddha Gaya for the Buddhists alone is estimated to be US Dollars 10 million in today’s currency. She supported many other projects including the purchase of properties in India and the UK. The Anagarika referred to her support as “unparalleled generosity”.

While all of the activity was taking place in Honolulu at the Pure Land Buddhist Temple in the early 1900s,Mary Foster was also paying attention to struggles in Asia. Her constant communication with Anagarika Dharmapala kept her apprised of what was happening in Sri Lanka and India and particularly with Anagarika’s struggle in Buddha Gaya. She continually supported his projects, both financially and spiritually, believing that his work had great meaning and would develop into something of value to Buddhists and many others around the world.

The Maha Bodhi Society, begun by Dharmapala in 1891, still has a major presence in Buddha Gaya and is regarded as the host organization to pilgrims and other visitors to the sacred temple. The society was formed initially to bring the Mahabodhi Temple management into Buddhist hands after it was lost so long ago to the Muslim invasion (1200 C.E.) and later to a Hindu sect, followers of Shiva, who took over the structure after its abandonment. The struggle for control between the Buddhists and the Shaivites lasted from 1891 to 1951 when a Temple Management Committee was finally created. The committee consists of three Buddhists, three Hindus and an elected official of the Buddha Gaya district. The constitution of the committee was a compromise not satisfactory to anyone, but it was the solution offered by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to resolve the sixty-year battle for control.

When Dharmapala came to Buddha Gaya, India was under the rule of the British and the people had been suffering from the imposition of Western Christian ideas, just as Sri Lankans and Hawaiians had been. Dharmapala thought he could reason with the British over the sacredness of Buddha Gaya and could convince them of the rightness of the Buddhist claims. Perhaps too idealistic about the British sense of fairness, what he hoped for did not happen for a long time and a number of reasons. First and most important, the British, who had been colonizing the sub-continent since the 1700s, were experiencing resistance from the Indian population. With the Indians tiring of their servitude, the British did not want to incite the Hindus at that point in history. Also, the Archaeological Survey of India, under the direction of Alexander Cunningham, had interests in the Ganges Plains and particularly in Bodh Gaya because of its antiquities. The more the ruins were tampered with, the less likely they would be able to offer up information about India’s past and to fulfil the mission of the society. Cunningham had a real interest in Indian history and particularly its Buddhist sites and monuments and he was an empathetic surveyor. However, it was also a period of great pilfering of sculptures and other valuable artefacts that were being sent home to the museums in London; it seems that Cunningham profited by his vast collection from Buddha Gaya. This “tradition” continued long after Cunningham left.

The idea of restoring the Buddhist Jerusalem into Buddhist hands originated with Sir Edwin Arnold after having visited the sacred spot in 1886. It was he who gave me the impulse to visit the shrine, and since 1891 I have done all I could to make the Buddhists of all land interested in the scheme of restoration

Dharmapala influenced by Sir Edwin Arnold’s Light of Asia asserted another claim. From his diary:

“The idea of restoring the ‘Buddhist Jerusalem’ into Buddhist hands originated with Sir Edwin Arnold after having visited the sacred spot in 1886. It was he who gave me the impulse to visit the shrine, and since 1891, I have done all I could to make the Buddhists of all land interested in the scheme of restoration.”

Dharmapala earnestly tried to reason with the Shaivites over the matter but to no avail. His efforts were thwarted at all turns for many long years.

Mary Foster may have visited the Buddha Gaya site but no tangible evidence for that assertion survives. She and Dharmapala discussed the ongoing machinations there and the need for assistance in supervising the reconstruction of the temple. They also discussed ways to convince the British authorities of the importance of Dharmapala and his associates having an ongoing presence there. In fact, Dharmapala spent seventeen years in Buddha Gaya without making very much headway in either of those efforts.

The actual struggle for the Mahabodhi spanned sixty years and because it was the main reason for Dharmapala and Mary Foster to meet initially, it is helpful to understand what was gained and lost in that struggle. Mary Foster contributed more than a million rupees (approximately $10 million by today’s account) over a period of forty years to the effort, and like Dharmapala, she never saw the resolution of the problem of the temple’s Buddhist jurisdiction.

Dharmapala’s initial inspiration for visiting Bodh Gaya was due to Edwin Arnold’s interest but it became his own personal lifelong project and passion. Arnold did not anticipate the obstacles that Dharmapala encountered in his attempts to recover the temple.

Dharmapala’s initial inspiration for visiting Bodh Gaya was due to Edwin Arnold’s interest but it became his own personal lifelong project and passion. Arnold did not anticipate the obstacles that Dharmapala encountered in his attempts to recover the temple.

He claimed that “the whole thing could be managed through amicable arrangements, between the various concerned groups.” However, in a study on the Maha Bodh Society in Bodh Gaya, author Alan Trevitick noted: “Neither Arnold nor Dharmapala understood the extent to which the temple was embedded in a system of longstanding local and regional relationships, at a concrete social level, and neither did they appreciate the extent to which the Buddha, and Buddhism, were encompassed, culturally and ideologically, by Hindu practice and ideas.”

Dharmapala was, at first, unclear about whom was in control of the temple when he arrived in January of 1891. The superintendent of the temple grounds, an employee of the government’s Public Works Department, told him that “the temple is under the control of the government but the Mahanta has the right of the management thereof.”

Then, in March of that same year and in response to Dharmapala’s inquiry into the possibility of purchasing the land on which the Mahabodhi Temple stood, George Abraham Grierson, the British Tax Collector at that time, told Dharmapala that “the temple belongs to the Mahanta, not to the Government” and that the Mahanta was unwilling to discuss its sale as the temple was sacred to him and not up for sale. At that point, Dharmapala returned to Ceylon and formed the Maha Bodhi Society to pursue his dream of returning the sacred site in Buddhism to Buddhists.

Dharmapala left Bodh Gaya in 1893 because he was invited to attend the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago. On his return home from that momentous event, he met Mary Foster in Honolulu and that meeting gave the young Sri Lankan the confidence and the promises of financial support that he would need to energize his project in Buddha Gaya. After his auspicious meeting with Mary Foster, Dharmapala travelled to Japan where he was given a tenth-century statue of the Buddha that the donors wanted installed in the Mahabodhi Temple.

On February 25, 1895, Dharmapala and three Sinhalese monks carried that statue to the temple in Bodh Gaya and attempted to set it up in the upstairs alter room. There ensued a confrontation with the Mahanta’s attendees and the statue was removed to the open courtyard downstairs. The police were finally brought in and the matter presented to the local British magistrate who heard the various versions of the event.

Dharmapala filed a legal petition with the magistrate. World spread to the British viceroy, Lord Elgin, who then travelled to Bodh Gaya to investigate the situation. After visiting the Mahabodhi Temple, the viceroy was disturbed that the Buddhists were not being allowed to worship there. In the meantime, the statue that Dharmapala had brought was missing. It was quickly found and reinstalled in the courtyard by the Mahanta’s men, but that deed alone had consequences in court.

During the court proceedings, it was established that Hindu worshipers did not enter the temple because it was considered a Buddhist shrine. It was shown, however, that the Buddha had been absorbed into the Hindu pantheon as an avatar of Vishnu. The case surrounded the Buddhist’s right to worship in the temple and the assault on them by the Hindus.

During the court proceedings, it was established that Hindu worshipers did not enter the temple because it was considered a Buddhist shrine. It was shown, however, that the Buddha had been absorbed into the Hindu pantheon as an avatar of Vishnu

The assailants were found guilty, so the Mahanta appealed. In the appeal, the issue of proprietorship became the focus and, then, whether or not Dharmapala had committed an illegal act by “trespassing” onto the temple grounds to worship. It was determined that Dharmapala had the right to worship and those who had prevented him were found guilty. The Hindus once again appealed to the higher court in Calcutta. The Hindus won the appeal and Dharmapala was forced to remove the Buddhist statue to the Burmese rest house.

The struggle for the Mahabodhi Temple continued for over sixty years and Mary Foster supported Dharmapala in all of his efforts regarding it. Mary was ecumenical, open-minded, and pluralistic. Dharmapala’s growing rigidity and intolerance toward the Hindus and their claims were counter to her own beliefs and, yet, she wholeheartedly supported his position. It seems that he had grown frustrated and had tried more “radical” means. If Mary recognized that Dharmapala was unreasonable on some points, she never revealed it in her writings to him. Perhaps she did not fully realize the ramifications of Dharmapala’s actions and his methods. It is possible that she was blinded by her steadfast belief in his motives and intentions. We will never really know what she felt about the Bodh Gaya project but we do know that she was sad not to see its resolution. She wrote about the matter to Dharmapala toward the end of her life. In 1927, she expressed, “For all your hard work and effort, it is unfortunate to receive no positive outcome. Perhaps the time will come when there will a resolution that will be satisfactory to you and will have great benefit to Buddhists everywhere.” As for Dharmapala, surely, he was drained by his personal forty-year battle for the Mahabodhi Temple. Overwhelmed by his own impending death, he finally surrendered to the fact that he would not live to see its completion.

Extracts from the book “Searching for Mary Foster” by Patricia Lee Masters

18 Apr 2024 2 hours ago

18 Apr 2024 3 hours ago

18 Apr 2024 3 hours ago

18 Apr 2024 3 hours ago

18 Apr 2024 4 hours ago