Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-26 02:11:00

The fifties and sixties were clearly epoch-making decades for much of the Western world and particularly for the United States. Almost overnight, the bourgeoisie, so accustomed to their way of life, found their culture eroding with the onslaught of the bohemians, the heroes of the counterculture who found their icons in the novels of Norman Mailer and the Beat Generation and the politics of Abbie Hoffman. But these were relatively prosperous years, probably the most prosperous of 20th century American life. David Brooks, in his clear accessible account of this phenomenon, Bobos in Paradise, contends that what transpired was the substitution of one way of thinking for another, a substitution that was short-lived, as the return of the corporate culture of the seventies and the eighties proved. Probably the best illustration of this shift can be found in the movies. In 1967, The Graduate, one of that year’s most successful films, depicted its hero in the form of Benjamin Braddock, who rebelled against conformity and the sexual depravity of the WASP (White Anglo Saxon Protestant) middle-class; 20 years later, its director, Mike Nichols, created a hero out of a stockbroker’s secretary who finds her way to the upper echelons of corporate America in Melanie Griffith, with Working Girl. From the one to another, there was a shift, from the bohemian values of the sixties to the bourgeois values of the eighties.

The fifties and sixties were clearly epoch-making decades for much of the Western world and particularly for the United States. Almost overnight, the bourgeoisie, so accustomed to their way of life, found their culture eroding with the onslaught of the bohemians, the heroes of the counterculture who found their icons in the novels of Norman Mailer and the Beat Generation and the politics of Abbie Hoffman. But these were relatively prosperous years, probably the most prosperous of 20th century American life. David Brooks, in his clear accessible account of this phenomenon, Bobos in Paradise, contends that what transpired was the substitution of one way of thinking for another, a substitution that was short-lived, as the return of the corporate culture of the seventies and the eighties proved. Probably the best illustration of this shift can be found in the movies. In 1967, The Graduate, one of that year’s most successful films, depicted its hero in the form of Benjamin Braddock, who rebelled against conformity and the sexual depravity of the WASP (White Anglo Saxon Protestant) middle-class; 20 years later, its director, Mike Nichols, created a hero out of a stockbroker’s secretary who finds her way to the upper echelons of corporate America in Melanie Griffith, with Working Girl. From the one to another, there was a shift, from the bohemian values of the sixties to the bourgeois values of the eighties.

In the hands of the masters, the middlebrow and the lowbrow is formalised: baila turns into The Moonstones, Dalreen Suby enters

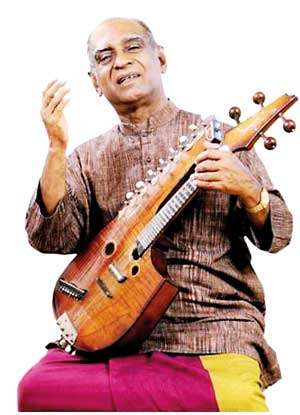

Such shifts are not rare, and are almost certainly reflected in the culture of a particular era. It’s interesting, thus, to note that while Abbie Hoffman was ranting and raving about the virtues of revolutionary politics and the Beatniks were hailing the LSD and drug culture of the fifties and sixties, Sri Lanka, conversely, faced a resurgence of bourgeois values. It was in the fifties that the efforts of the likes of Devar Surya Sena led to the creation of a cultural sphere. Led by the offspring of the upper class, these preservationists laid the bedrock for the emergence of that sphere, despite the errors they made when formalising the same culture they sought to preserve. In the United States the fifties and sixties had become the repository of revolution, of bohemia, of countercultural rebellion; in Sri Lanka, those decades would become the repository of the formal, conservative, middle-class, and petty bourgeois culture, the culture which was seen most discernibly in the films of Lester James Peries, the songs of Amaradeva, the plays of Sarachchandra, and the ballets of Chitrasena. While liberal and Westernised and modernised at the outset, these art forms were tinged with the middle-class puritanism of the audiences that patronised them. That most of these pioneer artists hailed from the petty bourgeoisie helped fuel this dichotomy, between modernism and traditionalism, even further. Premaranjith Tilakaratne recounts in his memoir Durgaya that when he got the great Sarachchandra to listen to the songs from West Side Story, the latter had just one reply to give: “It is nothing but cacophony!” This was not an era of polyphony, let alone cacophony: it was the era of the formal culture, patronised by the children of 1956, the rural bourgeoisie and the urban petty bourgeoisie, who were soon to become (as the novels of Karunasena Jayalath showed) the heroes of the art forms which had until then depicted them as props and supporting players. That Lester Peries’s most successful film until then was Golu Hadawatha, which valorised this milieu, is no cause for wonderment. It was inevitable in a way.

Such shifts are not rare, and are almost certainly reflected in the culture of a particular era. It’s interesting, thus, to note that while Abbie Hoffman was ranting and raving about the virtues of revolutionary politics and the Beatniks were hailing the LSD and drug culture of the fifties and sixties, Sri Lanka, conversely, faced a resurgence of bourgeois values. It was in the fifties that the efforts of the likes of Devar Surya Sena led to the creation of a cultural sphere. Led by the offspring of the upper class, these preservationists laid the bedrock for the emergence of that sphere, despite the errors they made when formalising the same culture they sought to preserve. In the United States the fifties and sixties had become the repository of revolution, of bohemia, of countercultural rebellion; in Sri Lanka, those decades would become the repository of the formal, conservative, middle-class, and petty bourgeois culture, the culture which was seen most discernibly in the films of Lester James Peries, the songs of Amaradeva, the plays of Sarachchandra, and the ballets of Chitrasena. While liberal and Westernised and modernised at the outset, these art forms were tinged with the middle-class puritanism of the audiences that patronised them. That most of these pioneer artists hailed from the petty bourgeoisie helped fuel this dichotomy, between modernism and traditionalism, even further. Premaranjith Tilakaratne recounts in his memoir Durgaya that when he got the great Sarachchandra to listen to the songs from West Side Story, the latter had just one reply to give: “It is nothing but cacophony!” This was not an era of polyphony, let alone cacophony: it was the era of the formal culture, patronised by the children of 1956, the rural bourgeoisie and the urban petty bourgeoisie, who were soon to become (as the novels of Karunasena Jayalath showed) the heroes of the art forms which had until then depicted them as props and supporting players. That Lester Peries’s most successful film until then was Golu Hadawatha, which valorised this milieu, is no cause for wonderment. It was inevitable in a way.

Definitive eras

What made these two decades the definitive eras of cultural renaissance, of the formal culture that is, was economic prosperity on the one hand and social puritanism on the other. Prosperity and Puritanism: these were the two factors which spurred an entire era. The petty bourgeoisie had been emancipated by Sinhala Only. The groundwork for that revolution had been laid down, as I wrote before, by the offspring of the Anglican elite, the Devar Surya Senas and the Hurbert Rajapaksas whose work would be taken over by the Sunil Shanthas, the Lester Perieses, and the Amaradevas. What 1956 did was to amalgamate the results of these efforts, which had been transformed into a definitive cultural renaissance, with the traditionalism and class prejudices of the milieu which led the Sinhala Only revolution, the rural bourgeoisie and the urban petty bourgeoisie. When you watch Lester’s films, particularly those from the sixties, you can spot out this traditionalist streak even in his most daring work: both Golu Hadawatha, which valorises young love, and Delovak Athara, which valorises the downtrodden and the unprivileged (it was Philip Gunawardena’s favourite movie), don’t go beyond the middle-class canvas they revolve around. In this sense the zeitgeist of this period was captured succinctly in Ran Salu, Lester’s most religiously saturated film, which brings the good/bad binaries of village life (exemplified by P. K. D. Seneviratne’s script) to the streets of Colombo 7, through the acting of Punya Heendeniya. (The Ceylon depicted in Ran Salu, as one reviewer put it, was a Ceylon full of affluence and middle-class aspirations. Perhaps he may not have seen a paradox in the intermingling of that prosperity with the puritanism of Punya’s character, and how the triumph of goodness does not clash with the aspirations of this middle-class.)

The Moonstones and Dalreen Suby

In the hands of the masters, the middlebrow and the lowbrow are formalised: baila turns into The Moonstones, Dalreen Suby enters the scene and apotheosises the meaning of nightclub music, on the one hand, while on the other, the second generation baila performers, M. S. Fernando and Anton Jones in particular, continue to pander to a more populist crowd. ‘Mango Kalu Nande’, which highlights and parodies a division between the householder and the servant (a division which would be sustained by the Clarence Wijewardenas and the Annesley Malawanas of this period), becomes the first Sinhala song to be broadcast on the English service of Radio Ceylon. The coastal belt, from Chilaw to Mount Lavinia, transforms kaffiringa into a formalised musical genre, and Neville Fernando, the pop voice of the fifties, effectively gives way to Clarence and Annesley. The middle-class of these two decades, lulled by economic prosperity, indulge in their bourgeois values even further, while on the other side of the world Vietnam and the Civil Liberties Union would put a further strain on the American economy and social sphere. We were a world away, happily continuing with a separation between the jana and the janapriya. It would take an entire decade for the janapriya sensibility to shift, mainly through Jothipala, who would take that sensibility to the populist masses, away from Clarence’s milieu.

In the seventies, and in pretty much every cultural sphere, including the movies, there was change: rampant, raging, and unforgiving. The complacent conservatism of the sixties, in the popular culture, yielded to a more humanitarian, liberal, slightly leftist streak. This was the era of Anton Jones, who sang about ‘Maru Sira’ and the cyclone of 1978 and the ‘Kanthoruwa’which fermented sloppiness, apathy, and laziness, and the era of Jothipala, who crooned about love unhindered by class origins. To be sure, The Moonstones, which had now transformed into the Super Golden Chimes, continued with their separation of the householder and the servant, though with much less vigour than before. (Moving away from ‘Mango Kalu Nande’, they instead sang ‘Kanda Surinduni’, ‘Ma Adare Nangiye’, and one of my favourites from these years, ‘Sudu Menike.’ They did not bother with the householder and the servant, in other words; they celebrated, blissfully, casually, the sights, the sounds, and the clashes of their personal lives.) But this decade entailed a paradigm shift. The artists of the fifties and sixties had been adamant on sustaining a divorce between the jana and the janapriya. The seventies, by contrast, saw a coming together of these two cultural streams.

The complacent conservatism of the sixties, in the popular culture, yielded to a more humanitarian, liberal, slightly leftist streak

It happened in unprecedented, almost unheard of ways. Mahagama Sekara and Somadasa Elvitigala teamed up to conjure a song for Indrani Perera and the Three Sisters: “Gaala Suwanda Rasa Handun” (its exuberance and refreshing pace might have almost been composed by Clarence Wijewardena).

Shelton Premaratne got together with Father Marcelline Jayakody and Dharmasiri Gamage for a song which brought together Nanda Malini and Dalreen Arnolda: “No East No West - Rangum Gayum Wayum.” (Father Jayakody and Dalreen were given the English section, while Gamage and Malini got the Sinhala section.) Having been shunned by filmmakers, for the crime of “bastardising” and “corrupting” the sarala geeya, Clarence found work in the film industry through H. D. Premaratne, who adapted the Ummagga Jathakaya to Sikuruliya and thus revitalised Swineetha Weerasinghe’s career. Amaradeva, having tried his luck with him once before, finally composed a song for Jothipala: “Kanden Kandata” (from Tharanga). These were quirks, yes, but over time they became more and more frequent. It is from here, thus, that we must explore that tragedy I outlined at the beginning of this series of essays: that while the janapriya sensibility continues, unabated and fresher than ever, the jana sensibility, which met the janapriya long, long ago, has stalled. How, why, and wherefore this came about, I leave for the next piece.

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

US authorities are currently reviewing the manifest of every cargo aboard MV

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul