Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-19 06:03:00

Operative paragraph 6 of Resolution 30/1 of the Human Rights Council, adopted on October 1, 2015, refers specifically to “Commonwealth and other foreign judges”. This is the Sri Lanka Government’s unequivocal commitment to the international community. It is not an obligation imposed on us by any external agency. On the contrary, it is the Government’s own pledge, embodied in a Resolution co-sponsored by it.

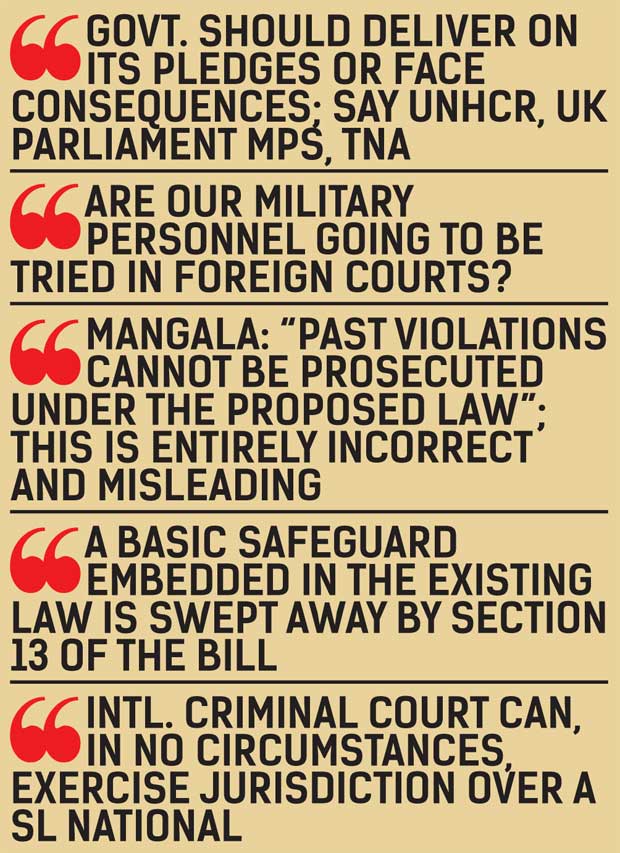

To repudiate this solemn commitment by pronouncements, however strident, within the country is both insincere and futile. The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, several other senior officials of the United Nations system, Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, the Tamil National Alliance, spokespersons for the Tamil diaspora and others have insisted in recent months that the Government should deliver on its own pledges, or face the consequences.

The proposed legislation explicitly envisages contexts in which members of the Sri Lankan military are subjected compulsorily to the jurisdiction of courts of foreign countries. We are, then, moving decisively from foreign judges coming to Sri Lanka to try our Armed Forces, to our military personnel being tried away from their own soil by the courts of other countries.

No one can deny that this is the plain effect of Article 9 (2) of the International Convention. It provides as follows: “Each State Party shall take such measures as may be necessary to establish its competence to exercise jurisdiction over the offence of enforced disappearance when the alleged offender is present in any territory under its jurisdiction.”

Thus, any member of the Sri Lankan military, found for any reason within the territory of a country which is a signatory to the Convention, will be tried by the courts of that country. This is not a mere discretionary entitlement of that country but an imperative duty imposed on it by the terms of the Convention.

This cannot happen under the present law. The legal position, however, changes drastically with the enactment of the new law which is expressly intended “to give effect to the International Convention”.  "The proposed legislation explicitly envisages contexts in which members of the Sri Lankan military are subjected compulsorily to the jurisdiction of courts of foreign countries. We are, then, moving decisively from foreign judges coming to Sri Lanka to try our Armed Forces, to our military personnel being tried away from their own soil by the courts of other countries"

"The proposed legislation explicitly envisages contexts in which members of the Sri Lankan military are subjected compulsorily to the jurisdiction of courts of foreign countries. We are, then, moving decisively from foreign judges coming to Sri Lanka to try our Armed Forces, to our military personnel being tried away from their own soil by the courts of other countries"

The explicit effect of section 8 of the proposed Bill is that, where a request is made by a foreign State, or on behalf of a foreign State, that a member of the Sri Lankan military or, for that matter, any citizen of our country be extradited to that State, the Government of Sri Lanka may be obliged to extradite that person if he is accused of the offence of enforced disappearance.

This is certainly not part of the present law. It is an altogether new obligation which will be incurred by the Government of our country as a direct consequence of enactment of the legislation now before Parliament to make the International Convention operative within the legal system of Sri Lanka.

Article 11(1) of the Convention gives a State Party in the territory under whose jurisdiction a person alleged to have committed an offence of enforced disappearance is found, the right “to extradite that person or surrender him or her to another State in accordance with its international obligations”. Apparently, this, too, is acceptable to the Government.

Minister Samaraweera declares, in a sub-heading of his article, that “The Bill has no implications on our Extradition Laws”. This flies in the face of several clear provisions of the Bill which expressly purport to make significant changes in respect of the laws governing the extradition of persons from Sri Lanka.

Where there is an extradition arrangement made by the Government of Sri Lanka with any Convention State, such arrangement is deemed for the purposes of the Extradition Law, No. 8 of 1977, to include provision for extradition in respect of offences under the new Bill (section 10).

Even where there is no extradition arrangement in force, the new Bill purports to make provision in this regard. It declares, in section 11, that “Where there is no extradition arrangement made by the Government of Sri Lanka with any Convention State, the Minister may by Order published in the Gazette, treat the Convention, for the purposes of the Extradition Law, No. 8 of 1977, as an extradition arrangement, made by the Government of Sri Lanka with the Convention State providing for extradition in respect of the offences under this Act.”

A basic safeguard embedded in the existing law is swept away by section 13 of the Bill. If the offence with regard to which extradition is sought, is an offence of a political character, extradition is not permissible in keeping with the current law. This salutary principle, involving a crucial measure of protection for cogent reasons of public policy, will no longer apply, once the proposed Bill is passed.

I do not accept this proposition. There is real danger of Sri Lankan military personnel in the physical custody of a Convention State being surrendered to the International Criminal Court.

The governing provisions of the Convention in this regard are Articles 9(2) and 11(1).

The former provides that “Each State Party shall take such measures as may be necessary to establish its competence to exercise jurisdiction over the offence of enforced disappearance when the alleged offender is present in any territory under its jurisdiction, unless it extradites or surrenders him or her to another State in accordance with its international obligations or surrenders him/her to an International Criminal Tribunal whose jurisdiction it has recognised”.

The effect of the latter provision is that “The State Party in the territory under whose jurisdiction a person alleged to have committed an offence of enforced disappearance is found shall, if it does not extradite that person or surrender him or her to another State in accordance with its international obligations or surrender him or her to an International Criminal Tribunal whose jurisdiction it has recognised, submit the case to its competent authorities for the purposes of prosecution.”

The operative criterion in this regard is not the nationality of the person sought to be extradited, but the international obligations of the Convention State having custody of that person. If the International Criminal Tribunal is one whose jurisdiction it has recognised, then the duty to surrender to the Tribunal is capable of being invoked. Persons in the custody of the Convention State may belong to a variety of nationalities, but they would collectively fall within the scope of the duty devolving on the Convention State to surrender, if that State is bound by recognition of the International Criminal Tribunal in question as part of its own obligations.

This danger is real and imminent. What is more, the obligation of surrender is not necessarily restricted to the ICC. The language used in the Convention is substantially wider. “An International Criminal Tribunal whose jurisdiction it has recognised” may apply, as well, to tribunals of a similar category, other than the ICC.

I have shown in my previous article that Resolution 30/1 of October 1, 2015, co-sponsored by the Government of Sri Lanka, is replete with compelling indications that the Government deliberately undertook the duty to take decisive action with regard to the past.

While the Preamble to the Resolutions stressed “the importance of a comprehensive approach to dealing with the past incorporating the full range of judicial and non-judicial measures, including individual prosecutions”, and called stridently for “mechanisms to redress past abuses and violations”, Operative Paragraph 4 “welcomed the commitment of the Government of Sri Lanka to undertake a comprehensive approach to dealing with the past”.

Among the specific obligations incurred by the Government of Sri Lanka is the setting up of an Office of Missing Persons to deal with past crimes. The proposed Bill is one of a series of measures which the Government is resorting to for the purpose of giving effect to these obligations.

In any case, the duty cast on the Government of Sri Lanka comes into play at the point when “a request is made to the Government of Sri Lanka for the extradition of any person accused of the offence” of enforced disappearance (section 8). Although the offence may have been committed prior to enactment of the Bill, the making of a request by a foreign government – obviously subsequent to the passing of the Bill – triggers the provisions in the legislation, and deprives of substance the argument based on retro-activity. It is a mere red herring across the trail.

UNHRC Resolution 30/1 “takes note with appreciation of the oral update presented by the United Nations High Commissioner to the Human Rights Council at its 27th session, the report of the Office of the High Commissioner and its investigation on Sri Lanka.”

The High Commissioner has been far from reticent about the gravity of the crimes allegedly committed by the Armed Forces of Sri Lanka, and the stark issue of criminal responsibility. He stated at a Press conference in Geneva: “The severity of the crimes was most astonishing”.

The degree of bias and prejudgement is quite manifest. On the subject of genocide, the High Commissioner, while stating that this is something they do not perceive to have occurred in Sri Lanka at this stage, went on the declare: “That is not, however, to say that at a subsequent stage, it is implausible”. The Report specifically says that, if established before the hybrid court that was proposed, “many of these allegations may amount, depending on the circumstances, to war crimes”.

The High Commissioner proclaimed, at a media briefing in Geneva, that the findings are “of a most serious nature”, involving as they do a pattern of systemic and flagrant violations.

The extent of jeopardy to Sri Lanka’s Armed Forces is unmistakable.

The Report sets out, in direct terms, the finding that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the gravest offences were committed by our nation’s military.

The following assertions, quoted verbatim from the Report, are amply illustrative of the threshold of criminal liability envisaged and the resulting depth of peril. “There are reasonable grounds to believe that the Sri Lankan security forces and paramilitary groups associated with them were implicated in unlawful killings carried out in a widespread manner against civilians”. “OISL documented long-standing patterns of arbitrary arrest and detention by Government security forces, which often reportedly led to enforced disappearances and extra-judicial killings”. “OISL documented brutal use of torture by the Sri Lankan security forces”. “The information gathered by OISL provides reasonable grounds to believe that rape and other forms of sexual violence by security forces personnel was widespread”.

These sweeping statements leave no room for doubt as to the intended consequences. Against the backdrop of these attitudes reflecting total lack of objectivity, the public are the best judges of the justice of leaving the fate of our country’s Armed Forces in the hands of foreign judicial tribunals.

sach Tuesday, 08 August 2017 09:51 AM

Yahapalanaya is treason!

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul

A recent post on social media revealed that three purple-faced langurs near t

10 Apr 2024

09 Apr 2024