Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-19 22:36:00

All things considered, music is one of the most acute markers of cultural identity and sophistication in any given society. One need not be a theorist or practitioner in the field to realise this. As such, the biographies of composers, lyricists, and vocalists, not to mention sound engineers and even studio owners, are inextricably woven into the history and evolution of those identities. What would Western civilization be without Mozart and Beethoven, for instance?

All things considered, music is one of the most acute markers of cultural identity and sophistication in any given society. One need not be a theorist or practitioner in the field to realise this. As such, the biographies of composers, lyricists, and vocalists, not to mention sound engineers and even studio owners, are inextricably woven into the history and evolution of those identities. What would Western civilization be without Mozart and Beethoven, for instance?

For me, music is therefore at once a promoter of cultural uniqueness and fluidity. And for me, three names crop up when one tries to validate this thesis in the context of our culture: Amaradeva, Clarence Wijewardena and Premasiri Khemadasa

One of the very first articles I wrote to this paper was on Khemadasa (“Premasiri Khemadasa’s lost songs”). In it, owing to my immaturity, I broke down the man’s career to three distinct periods, corresponding to certain shifts in the man’s outlook on his field. I realise now that such an exercise, though certainly befitting of an academic, can only be futile if not simplistic if undertaken by an amateur like me. It makes one miss the bigger picture, the full worth, of the person being written on. The truth of the matter is, then, that when it comes to the biography of someone like Khemadasa, one has to start from the beginning. There are no shortcuts.

Premasiri Khemadasa Perera was born in Wadduwa, the youngest alongside 12 other siblings, in 1937. He was not born to an affluent family: his father died when he was seven and from that point on it was his mother who looked after the household. Owing to economic reasons, there was never much interest shown towards the education of the children, a fate which befell young Premasiri despite the fact that he maintained strong academic credentials at school.

It was around this time that he chanced across, and bought, a cheap flute. Like Oscar Matzerath, the hero who carries a toy tin drum in Gunter Grass’ classic novel, young Premasiri formed an inextricable bond with that flute. In his biography of the man, Eric Iliyaparachchi writes of how, as a boy, he would entertain train passengers with it on the way to Colombo from his hometown, and how those passengers, who happened to be port labourers, would buy him the platform ticket to exit the station. That flute would, not surprisingly, become a reminder of a rather strained childhood.

These were happy times, though they were almost always undone by his schooling, for while he was academically inclined, he never got the recognition he deserved from his teachers. This, coupled with the inevitable pressures of growing up with 12 elder siblings (who would constantly break his beloved flute), meant that his attachment to his instrument bred in him a love, an intense love in fact, towards music.

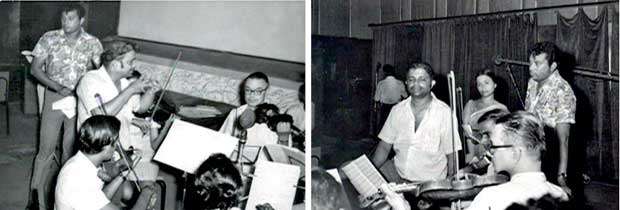

After entering the Radio Ceylon orchestra, Khemadasa, “young” no more, began his career properly in the field of film music. It is in here, and not in the symphonic pieces he would compose decades later, that we see him evolve as an original composer.

Film music at the time was nothing more than the art of transcribing some foreign (usually Indian) melody after adding some Sinhala lyrics. John de Silva’s theatre had found its cinematic equivalent in the Jayamanne brothers, and this found its way to film soundtracks. The 1950s moreover saw a plethora of vocalists from other parts of the world - America, Europe, even LatinAmerica - make their way to local airwaves. Local performers, enamoured by the exoticism of it all, merely added to the process of cultural plagiarism that the Jayamanne brothers had inadvertently initiated.

Film music at the time was nothing more than the art of transcribing some foreign (usually Indian) melody after adding some Sinhala lyrics. John de Silva’s theatre had found its cinematic equivalent in the Jayamanne brothers, and this found its way to film soundtracks. The 1950s moreover saw a plethora of vocalists from other parts of the world - America, Europe, even LatinAmerica - make their way to local airwaves. Local performers, enamoured by the exoticism of it all, merely added to the process of cultural plagiarism that the Jayamanne brothers had inadvertently initiated.

Whether or not Khemadasa determined at the outset to stray away from this trend, we cannot say. In any case, he was caught in a tentative battle between the populists, who went on borrowing from the outside world, and the exponents of the sarala geeya, who wanted a more original idiom in tune with our civilization.

When Madawala S. Ratnayake and Amaradeva transformed the jana kavi to the sarala gee, they cut down on the background music. This privileged the literary worth of a song, as opposed to its instrumentation, so much that, as in India, the sarala geeya here became an alternative to film music. As such it was the counterpoint to the film song, the popular ditties and ballads which, in Sri Lanka, had been plagiarized from India. It was a rift that could never be bridged, at least not until the 60s when the likes of Ratnayake and Amaradeva entered the cinema as poets and composers and challenged the Muttusamys and the Pandurangans who had dominated the field until then.

Khemadasa’s entry to the cinema has to be assessed against this backdrop. He sought to look beyond the popular balladeers, who privileged the vocalist, and the champions of the sarala geeya, who privileged the poet, and bring about a fusion between the two. But before everything, there was a cultural challenge he had to reckon with.

The Odi poet Fakir Mohan Senapati once observed that when the people of Odisha tried to read prose works, “they would try to sing the words and express surprise and irritation at not being able to find the rhyme or metre.” What was true of that territory was true of ours too: we preferred poetry to prose. Perhaps that is why prose works, even during the Dambadeniya period, were never as popular as poetry was, here.

The indifference to Western classical orchestral music this gave birth to (owing to our dislike of aesthetic works which lacked poetry or vocal backing) was the challenge that Khemadasa had to face. While he faced it well, it was still not possible in Sri Lanka for this kind of musical purism to go beyond the critics. It needed a different sensibility. After all, we were not a country that had seen court composers, who spoke to the elite, the patrons of the arts. We were a country that had seen court poets, who spoke to the people, the consumers of the arts. This difference can help explain why Khemadasa’s later forays were lauded by the elite, yet ignored by the people.

In that respect, the man’s greatest contribution was in the territory he had started his career in. Admittedly, there had been much work done before on (film) music by other composers, a point that Eric Iliyaparachchi misses in his biography. The likes of Sunil Shantha and Ananda Samarakoon, for instance, had suffered for the sin of originality, faced obstacles very different to the ones that Khemadasa would face, and laid down the groundwork for their successors. The challenges they had to wade through were specific to their time, but having met them, these early pioneers became instrumental in helping the likes of Khemadasa to evolve later on.

And yet, even when one brushes aside these historical antecedents, one can only be amazed (as I am, always) by the length and breadth of the man’s works. From the opening, evocative bars of “Sulan Kurullo”(from Senasuma Kothanada) to the sharp and deft interplay of cello, harp, and drum in the sequence of the protagonist coming across the woman he marries to offer as a sacrifice in Nidhanaya,there is much in Khemadasa’s compositions, with or without a poetic veneer, which bespeaks to a higher consciousness, a higher level of sophistication.

The truth of the matter is, then, that when it comes to the biography of someone like Khemadasa, one has to start from the beginning. There are no shortcuts

M. S. Anandan, who shot Nidhanaya, told me that he was not a little frustrated by the decision of its director (Lester James Peries) to shoot a waltz sequence between the protagonist and his wife. “I badly wanted,” he candidly recounted, “to turn it into a musical number.” By “musical”, he meant the cha-cha, the twist, the swing. He could not have been moved by or impressed with Khemadasa’s waltz, which was so dazzling to me that even now, I am sorry that no one took the time to do a better recording. To be mesmerised by it, one requires both intellect and connoisseurship.

Indeed, so evocative was the music in Nidhanaya that no less a person than Sanuka Wickramasinghe alluded in “Saragaye” to the opening bars of the film’s main theme. Bathiya and Santhush had alluded to Bach’s “Air on the G String” in “Wasanthaye”, and to Beethoven’s 6th in “Ras Wihidena Samanaliyakuge”; in that sense, the closest to Bach and Beethoven a local performer could take from, in here, was Khemadasa.

I thus believe that in one point I was right in my last article on him: like Beethoven, Premasiri Khemadasa saw music in terms of its potential to liberate the artist from the corridors of tradition. It was this which motivated, right from the time he came across that cheap flute in his childhood, so much so that in the end, we cannot say that we are not all the richer for what he did. Or for that matter tried to do.

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul

A recent post on social media revealed that three purple-faced langurs near t