Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-16 21:36:00

Whenever the young people I happen to meet insist, by implication, that I speak with them in English, they are nervous, and not because I can speak the language well. (For the record, I stutter very badly.) Rather, it’s because they want to convince me, subconsciously, that they don’t want me to condescend to them when I speak that language and because they assume that I am more conversant with it, when I am not. They are exceedingly polite, aloof, always smiling, and never wont to the casualness with which they greet one of their own kind. They speak wonderfully well, and some of them write very well, but they can never let go of that lack of confidence which often comes with the pain of understanding that they have been alienated from the language from their birth. The rest of the world has an advantage over them, but they ignore that; since they can’t convince that world, they try to convince me.

Whenever the young people I happen to meet insist, by implication, that I speak with them in English, they are nervous, and not because I can speak the language well. (For the record, I stutter very badly.) Rather, it’s because they want to convince me, subconsciously, that they don’t want me to condescend to them when I speak that language and because they assume that I am more conversant with it, when I am not. They are exceedingly polite, aloof, always smiling, and never wont to the casualness with which they greet one of their own kind. They speak wonderfully well, and some of them write very well, but they can never let go of that lack of confidence which often comes with the pain of understanding that they have been alienated from the language from their birth. The rest of the world has an advantage over them, but they ignore that; since they can’t convince that world, they try to convince me.

Such first encounters leave me perturbed and the conversations that flow from these encounters and the many encounters I walk into later on leave me confused. It’s a curious contradiction at the heart of the milieu from which these young people come – they happen to hail from the ‘village’, yet they are situated in the ‘city’, because of which they have to be as ‘good’ as those around them – and it explains how we, and even those who teach us, treat English; with both respect and contempt. These youngsters love to write in that language, to speak it, but they also despise it for the gulf it opens up between them and the rest of the world. So much so that when they relapse to their own tongue – in my case and the case of the people I meet, Sinhala – they revert to the joviality that had eluded them in English. Sometimes I even sense strong undercurrents of contempt beneath their laughter whenever I stutter and stammer in my own language; they don’t hate me for it, yet they picture me as the city-bred babe the same way those from the city picture them as unsophisticated bumpkins. It’s a clash of civilisations, within a civilisation.

The Sinhala speaker, in such circumstances, treats the English speaker in much the same way that the English speaker treats the Sinhala speaker: in both cases it’s snobbery versus inability

Snobbery vs inability

The Sinhala speaker, in such circumstances, treats the English speaker in much the same way that the English speaker treats the Sinhala speaker: in both cases it’s snobbery versus inability. But because the English speaker in this country, like the English artist and critic and writer, is a minority, he is forced to be even more pronounced in his snobberies. I have been enthralled these past few years by various encounters with those who wield Sinhala and English so well that they put to shame anyone in the Sinhala or English cultural spheres who operate in one language to the exclusion of the other, but these encounters have been few and far in-between, because bilingualism in this country is fast disappearing. That’s why, I suppose, the way each cultural sphere treats and regards the other, even in otherwise ordinary and unexceptional conversations, fascinates me so much. It’s an eternal battle of wit versus grit; the Sinhala speaker, like the poor child in many of our children’s movies, has the latter; the English speaker has the former. In other words, it’s intelligence versus ability, or book-smart versus street-smart.

Whenever an English play depicts a ‘native’ speaker (Sinhalese, Tamil, or Sikh), it tends to depict him unflatteringly; he’s so stupid that he can only act without using his mind, and is hence made out to be a mechanistic robot. Whenever a Sinhala play depicts an English language speaker it too depicts him unflatteringly, only this time he is more often than not bespectacled, is clad in suit and coat, and speaks pompously. This is true of other art forms too; in an episode of Bodima I saw when I was young, an English teacher who ostensibly refuses to speak in Sinhala does so when the most aggressive resident in the bodima tries to attack him over a misunderstanding. This attitude – that the pretenders among us, who project their snobbery by explicitly desisting from the vernacular, can be made to exit their snobbery by force – is refreshing because it has been made use of in interesting ways, and even parodied: towards the end of Giriraj Kaushalya’s Sikuru Hathe, when our ‘hero’ (Vijaya Nandasiri) is being chased by Suraj Mapa, he runs into a foreigner, who he derides for his clumsiness (“Koheda pol booruwo yanne?”), and who returns that derision, unexpectedly, in his own language (“Thamuse ne yako pol booruwa!”). But when the English artist satirises the Sinhala speaker, the effects are ominous, very often sinister and insidious.

Stories we enjoyed

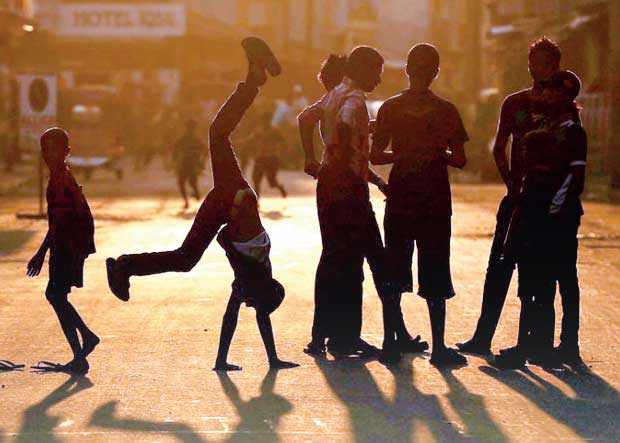

From an early age, the stories we learned and enjoyed the most ended in the triumph of strength and goodness. No matter how hard we tried to get out of these stories, they stayed with us as we graduated to other art forms; television, the theatre, and finally, the movies. The popular cinema plays on the hopes and expectations of popular audiences, so there this triumph of strength was squared with another motif; the triumph of the doer. We were more inclined to the stories of Twain and Stevenson. We loved, in other words, to see doers. Not because we hated to think, but because we wanted to act. Even the popular culture we grew up on accentuated this quality, and when the heroes we fawned on lost their strength, and had to resort to their intelligence, we revelled in seeing them use that intelligence to get out of whatever situation they were in. (Asterix and Obelix, when they ran out of their arishta, compelled this attitude; they were weak, yes, but they tided over their weakness by resorting to the most obvious plans and escapades.)

The triumph of the strong, even when the strong are put down by outside forces, is what characterises the Sinhala theatre and film; it’s the strong who is vindicated, not because they are physically strong, but because there is goodness within them. The thinkers are characterised as weaklings; they are doomed to be cast aside because they can’t be anything more than submissive receptacles, that is, yes-men and cheerleaders, to the hero. It’s not a class rift that we see being sustained in these works of art, to put it clearly, but a world in which the strong are good and the bad are defeated once their henchmen, and their sources of power, are exhausted. In the English cultural sphere, however, a different sensibility crops up; despite the intentions of the most sincere playwright, what eventually transpires is that the ‘vernacular’ man (or woman) is put down as stupid and ignoble. Curiously enough, here too the ‘strong man’ happens to be, like his counterpart in the Sinhala cultural sphere, the Sinhala speaker, only this time the strong one isn’t vindicated, the weak one is; the bespectacled, naive babe from the Sinhala play is now turned into a champion, at the cost of the entire Sinhala-speaking demographic.

Whenever an English play depicts a ‘native’ speaker (Sinhalese, Tamil, or Sikh), it tends to depict him unflatteringly; he’s so stupid that he can only act without using his mind, and is hence made out to be a mechanistic robot

When the typical teenage dramatist/writer resorts to the comedic skit, political or otherwise, at a school function, I’ve noticed that he tends to gravitate towards satire and poke fun at the symbols of modernity: the telephone, the mobile phone, the fax machine, Facebook. (One such play I happened to come across re-enacted a scene right out of Sakra’s abode – Sakra the God – where divine figures communicate with their agents in the human world through all those symbolic devices.) It’s an attempt at getting us to laugh, and we laugh with these young idealists, because they are sincere and innocent about what they’re doing. They need an outlet to assert their convictions through the arts, and they do this by turning banality into hilarity. It’s the kind of attitude that greets me whenever I betray my lack of knowledge of my culture in front of them: they grin, they comfort me by telling me what’s right, but they laugh at me and I laugh with them. Sometimes I wish the English artiste would leave them alone, but no; that artiste always puts down these Sinhala speakers, not to make us laugh with them, but to make us laugh at them, rather crudely.

UDAKDEV1@GMAIL.COM

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul

A recent post on social media revealed that three purple-faced langurs near t

10 Apr 2024

09 Apr 2024