Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

Last Updated : 2024-04-18 22:44:00

From Paranthan, the road to Vallipuram is rich and green. Great expanses of paddy stretch out before you, clumps of palmyrah dot the land and little streams of water trickle by. As we near the fighting, paddyfields give way to broken buildings and blasted vehicles. Twisted trees and uprooted trunks line the way. Everything is covered with a layer of brown dust. An occasional boat lies stranded on either side of the road, reminders of a last desperate attempt by the Tamil Tigers to hold back the tide. Blasting a reservoir in the path of the advancing Sri Lanka army, Tiger cadres counterattacked in boats, riding upon a wall of water. The water however, has receded and the Tigers have retreated.

As you enter the Kanishta High School, Vallipuram, the first thing you see is a brightly coloured board. Written at the top in vivid blue letters, is an inscription in Tamil.

Our students (Our Lifeblood ) ,

Those who Sacrificed their Lives

For the Freedom of this Land

Listed across the board are the names of the students of Kanishta High School who have died in the fighting. To make sure that their fellows do not forget, we are told where each student was from, what his LTTE code name was, when he died, where and in what operation.

The school is now occupied by the 58th Division of the Sri Lanka army. It is the first stop for those fleeing the fighting and they are brought here straight from the line.

A huge compound lies before us, lined on three sides by battered, ramshackle buildings. On one side are a set of classrooms, what was once the principal’s office is now a storeroom, piled high with sacks and boxes. On the left is a long low structure, open on every side and roofed with thatch. On the right is another series of buildings, now converted into kitchens and sleeping quarters. In the middle is a vast empty space, a small open tent at its centre. Nearby stands an ambulance, a Land Rover without wheels and two red buses. There is a roar of engines. The buses start up and trundle away.

At 8.45 am, the buses roll back in. Out stumble a ragged line of people, mostly women, children and old people. Tense and fearful, they look dazed and slightly lost. Most are drawn and dehydrated, many are clutching bottles of water. Nearly everybody is clinging onto bags and sacks, loaded with all their worldly goods. Their clothes are filthy, stained and spattered. Nearly all the children have sores and rashes. Strangely enough, there are very few young people, barely a handful out of 128.

The ambulance stands by, ready to rush the injured to hospital. The nearest hospital is Kilinochchi. Although the bunkers set up by the Tigers are still in place, it is now staffed by two civilian doctors and attendants. However, there are no wounded on this bus.

The IDPs are helped out of the bus by women soldiers, who lead them towards the long thatched area. While some wrestle with the bigger bags, the other women distribute biscuits, fruit drinks, bags of dates and sachets of glucose. The dates are for energy and the glucose is for dehydration.

Snatching at the biscuits, they tear at the wrapping, spooning the glucose into their mouths with their hands. Once they are seated a man in a yellow T-shirt begins an address in Tamil. They listen intently, wide eyed and open mouthed, wondering what is in store for them. There is hardly a murmur, even the children are quiet. Craning their necks to listen, they pause only to dip into their bags of food and guzzle water. Slowly they begin to nod their heads.

Once the address is over, we begin to hear their stories. Maria Kumari, a young woman of 29, had come all the way from Mannar, the north western tip of the island and ended up at Pudumathalan. She has both her two children with her, her three year old son Dinesh Kumar and her baby girl, Thireeshika. At first her eyes are closed and she just leans back against a chair. Gradually she begins to speak. As she talks, a smile lights up her fine features. For three days she has had no food, only gruel.

I was starving, my children were starving. Every day people are falling sick and people are dying, No food, no medicines, no water.

She had fled at night with her husband, wading across the Pudumathalan lagoon, the water chest high. Hearing the sound, the Tiger cadres had fired. So they remained where they were, waiting in the water till dawn. She stops talking to pour glucose down her throat. All I want now is to go home, to lead a normal life without fear.

By her side, an aged woman, gazes adoringly at a picture that she has been clutching from the moment she got down from the bus. It is a framed picture of the Baby Jesus and she had carried all the way from the Kilinochchi. It has been her protection, she tells us and “it has saved me.” Her name is Maria Poomani.

They wouldn’t let us come, she said. They shot at us, as she remembered she kept touching the Baby Jesus with her fingers. The rest turned back but we threw ourselves onto the sand and crawled on our bellies.

An old man sat staring into space, a shawl over his head. Another man, heavier and burlier, nodded in agreement.

Why are you leaving us, they asked. They said that we will be imprisoned, killed and tortured.

We did not think we would be treated so well.

In the adjoining partitions there are interviews taking place. It is here that the screening process begins. A man behind a desk asks questions. Everything is open and almost anyone can just walk in. Each individual and every family is registered and photographed. When the screening is over, everybody moves into the tent in the middle

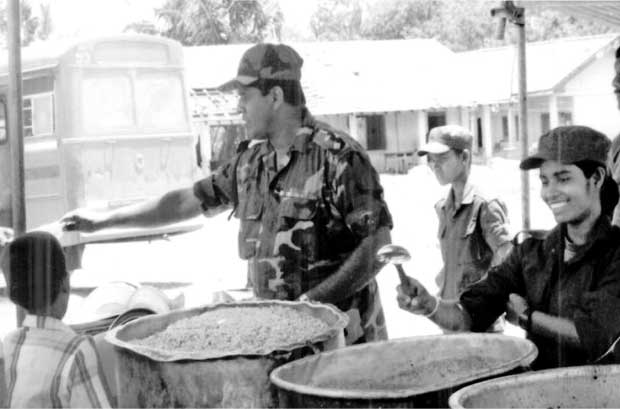

Staggering soldiers drag in steaming cauldrons of dhal, rice and soya and there is a rush towards the food. The children are first in line, holding out their plastic plates to the women soldiers. Once everyone has finished, they board the bus again for the next stage of their journey. They would travel down the A-9 road to Omanthai, two and a half hours away. Omanthai is the last checkpoint controlled by the army, from here the IDPs would be handed over to the government.

Private Saman Kumari had been one of the three women soldiers who had got off the bus. Along with her friends, Minoshi and Tharaki, she had met the refugees at the line. They always come at first light, she said. We give them water and search them and check their bags. They are frightened and so are we.

The male soldiers search the men, we search the women. As women, we feel sorry that they have to take their clothes off. They are ashamed and we feel their shame. At first we did not search anybody, we used to bring everyone straight here. Then the

bomb happened.

There was one woman, she was about thirty. We had looked at her bags but we had not searched her body. She told us that she had lost her gold jewellery. She started crying and everyone gathered around to help. I left the other women soldiers with her and went to eat. Then we heard the sound. All we could see was smoke. People were screaming and there were pieces of flesh everywhere. She had strapped the bomb to her stomach.

Before we used to pick up the children and carry them. We used to carry their bags.

Now we know. Even a small child can carry a bomb. Now we search everyone. Now we watch everyone. Some of the women don’t want to take their clothes off. So we tell them, you are women and so are we.

We felt so sad. We did so much. But we cannot fight, so this is all we can do for

our country.

From Vallipuram the buses speed through the rolling savannah of Sri Lanka’s Vanni region. Once the heartland of Tamil Eelam, now it is an empty landscape dotted with army posts. At 3.30 in the afternoon we arrive at Omanthai, the last checkpoint in the army controlled zone. Once the border post for leaving and entering Tamil Eelam, Omanthai consists of a series of parking areas and open sheds. Here the IDP’s bags are searched again and their possessions itemized. They are questioned, their identities checked and they are registered and issued with cards.

Everyone is seated on the ground. As the shadows begin to lengthen, a young man in a T-shirt and a baseball cap begins to speak. His tone is reassuring.

We know that the Voice of Tigers Radio have told you that your men will be killed and your women raped. No one will be taken away. None of you will be sent to prison. Our war is with your leaders, not you. You have been taken by force and kept by force. If you have any connections with the LTTE come forward and tell us now.

Nothing will happen to you. But tell us now before somebody else does.

When you go to the camps, there will be people who know you. Tell us now, so that we can trust you. If you don’t we will suspect you.

When he had finished speaking, almost everybody got up and moved to another spot. A small knot seated themselves in another group. There were five men and two girls. Amongst them I recognized some of those whom I had seen in the morning. They had been slightly apart, sitting on their own with strained, intense expressions. All were young and in good physical shape. They were all much better dressed than the others, some of their clothes were almost fresh.

When he had finished speaking, almost everybody got up and moved to another spot. A small knot seated themselves in another group. There were five men and two girls. Amongst them I recognized some of those whom I had seen in the morning. They had been slightly apart, sitting on their own with strained, intense expressions. All were young and in good physical shape. They were all much better dressed than the others, some of their clothes were almost fresh.

They were questioned one by one under the trees, their interrogators, smiling young men in jeans and T-shirts. Their manner was casual and friendly. As they talked, the cadres began to relax; the tautness gradually leaving their faces. There were smiles and even laughter. It seemed more like a social gathering, a picnic in the open air. The questions are gentle

but probing.

We were not allowed to ask their names or take their picture. One girl had brightly gilded earrings, which glinted in the afternoon light. She wore a long brown dress and her hair was tied up. She was 24 years old, a member of the Sodhiya regiment, one of the crack female fighting brigades. We asked her why she

had joined.

I joined because I left school early and stayed at home. My mother was angry with me and used to beat me. I joined to make her angry.

She had left her husband behind. As she spoke, tears glistened in her eyes. He was seized by the LTTE. I am very worried for him. Her leaders had told her that she must kill all Sinhalese. I did not expect to be treated like this, she said. They have lied to us.

We asked if she was still frightened. Smiling, she cocked her head and looked at us coquettishly. Whom should I be frightened of ?

Her words were echoed by a thin, wiry young man with buffed hair and shaved sideburns. We were taught that we would be tortured. It was in my mind. Unlike the others, he still had a closed, hidden expression on his face. He had signed up straight from school. He told us that he was a member of the computer wing and that he had joined for the salary.

Squatting on the ground, their families waited anxiously. The children were not crying now, they were playing with the sand. The same burly man I had spoken to earlier, told us that it was the first time he had seen a biscuit in several months. At Pudumatalan the beach had been their toilet, men and women squatting together in the sea, as many as fifty at a time. Relatives who had managed to get away had spoken to them by telephone. They told us that we would not be punished. That is why we are here. All I want to do now is to bathe.

Once the questions were over, the cadres were photographed against a spreading tree. When everything was finished, they picked up their bags and walked towards their families. I had thought that they would be treated as prisoners of war, so did they.

In the sheds on the other side queues were forming. Every item was checked and rechecked. An old man tapped me on the shoulder, do you work here ? Pointing to a big bandage on his ear, he asked in Tamil, where can I go to get some more medicine.

The final registration process took place in another shed, longer and lower than the rest. Long lines of tables run the length of the building, manned by women soldiers and a few policemen. Details were checked and noted and they were given cards and numbers. The silent tension had given way to animated gestures and a rising din. Clutching their newly issued cards, they handed over their numbers before climbing aboard the waiting bus.

By 5.45 everything was nearly over. As the sun began to set, the last bus started up. It would be the fourth and final stage of the journey, down the A-9 to Vavuniya. Their final destination would be the camps run by the government. They were now the concern of the civil administration.

As the engines rumbled, an old woman was doing her best to clamber on to the running board. Hauling herself up, she turned to berate a brawny soldier struggling with her numerous bags. Everybody grinned and looked away.

In less than 24 hours Sri Lanka’s IDPs would have crossed three sets of lines.

Historian, art historian and academic, Dr. SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda was one of the few non combatants allowed into the war zone during the final stages of the Eelam War (March - April 2009.) On his own initiative, he made an application to visit the conflict zone and was granted permission by the Defence Ministry. His essays and photos are based on firsthand experience and have been published in military journals and in the national and international media. His description of the

Historian, art historian and academic, Dr. SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda was one of the few non combatants allowed into the war zone during the final stages of the Eelam War (March - April 2009.) On his own initiative, he made an application to visit the conflict zone and was granted permission by the Defence Ministry. His essays and photos are based on firsthand experience and have been published in military journals and in the national and international media. His description of the

massive humanitarian operation conducted by the Sri Lanka Armywas first published in abridged form in The Independent (UK), on Wednesday 15 April 2009, entitled The Casualties of Sri Lanka’s Brutal Civil War. The publishes the original version in unedited form.

Add comment

Comments will be edited (grammar, spelling and slang) and authorized at the discretion of Daily Mirror online. The website also has the right not to publish selected comments.

Reply To:

Name - Reply Comment

On March 26, a couple arriving from Thailand was arrested with 88 live animal

According to villagers from Naula-Moragolla out of 105 families 80 can afford

Is the situation in Sri Lanka so grim that locals harbour hope that they coul

A recent post on social media revealed that three purple-faced langurs near t

10 Apr 2024

09 Apr 2024